Lessons from My Father: Grandpa Stanton

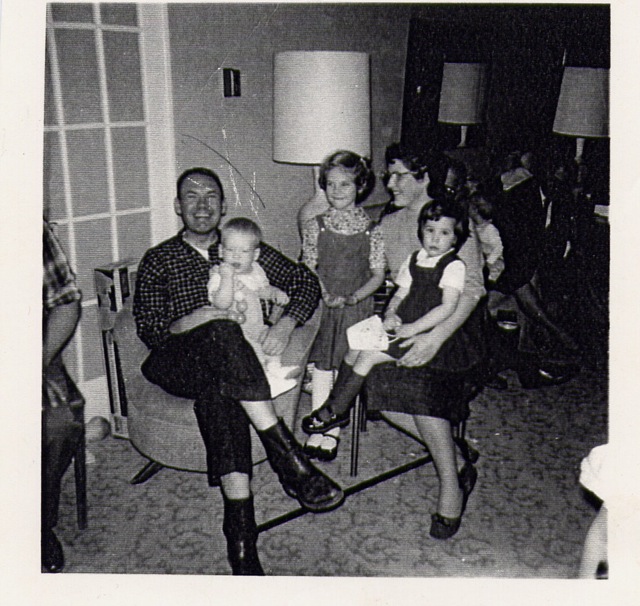

Once again, a packed June schedule means there’s been no time to prepare a post for today. So once again, I dug into old writing files and pulled out a chapter from Lessons from My Father. That’s the book about growing up with my dad who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis when he was 29 and wheelchair bound shortly thereafter. It’s also the book that landed an agent, but has yet to be published.

Today’s story comes from early in the book and in Dad’s illness. It takes place in a short span of time when Dad’s father lived with our family and then entered a nursing home. This story caught my eye because of the reference to the Little Store. At our high school class reunion, we reminisced about that same establishment, which was a neighborhood grocery store that operated in a converted garage.

But the story is about much more than sweet memories of the Little Store. It is about one of the many losses my parents experienced in the late 1950s and early 1960s. As a child, I didn’t understand how their dreams were snatched away, one after another. Now, as an adult, I marvel at their ability to keep going during those sad years.

Grandpa Stanton

Grandchildren are the crown of old men,

And the glory of sons is their fathers.

Proverbs 17: 6

“I’m goin’ to the Little Store. I’m goin’ to the Little Store.” A surge of satisfaction welled up from deep within me as I sang to myself. My small hand fitted perfectly into Grandpa’s big one, and I reined in my high spirits. I attempted to glide beside him in a dignified, graceful manner worthy of his presence, and at the same time I quivered with anticipation of the delight that awaited only one short block away.

“What are you going to buy with your nickel, Jolene?” Grandpa looked down from his great height with a smile.

I looked up at him, comforted rather than intimidated by his stature. I liked looking up to him, an act not necessary when I walked beside my father’s rolling chair. I pondered my answer while avoiding the cracks in the sidewalk. Notoriously clumsy, I didn’t want to trip and fall, ruining this delicious outing. “Whaddya think I should get, Grandpa?”

He always gave me, one of his only three grandchildren, thoughtful advice which my other grandpa with three times as many descendants to his credit never had the time to offer. “Do you like gum? You could buy a pack and share it with your family. Five sticks. You’d have just enough.”

Mentally, I flushed that idea. Grandpa had given me a whole nickel to spend on myself. No way was I going to share. “Nope, I don’t like gum.”

“Do you like candy bars?” he probed. I liked this about my grandpa. Mom didn’t have time to find out what I liked, and Dad didn’t always have the staying power. Neither of them had nickels to squander on candy from the Little Store, but Grandpa Stanton did, at least during this most fulfilling interlude, a short April to November, when he lived with us. He lavished upon his grandchildren the time, attention, and nickels they loved.

“Chocolate, lots,” I confessed.

“Do you like nuts?” He knew just the right questions, always.

“Uh-uh.” That I knew with certainty.

“Then I,” Grandpa counseled with great solemnity, “recommend a Milky Way.”

We walked into the Little Store, and I looked at the candy rack. Grandpa was right. A Milky Way was just what I wanted. I placed the candy bar and my nickel on the counter.

“This somebody special, Jolene?” Mrs. Manning asked as she rang up the sale. She recognized all the kids in the neighborhood. Most of them purchased candy and pop from the tiny shelves that lined the garage she had outfitted as a neighborhood grocery store. The Stanton kids only came for a loaf of Wonderbread or a half-gallon of milk when those staples ran out mid-week. She correctly deduced that this candy purchase was a noteworthy event. I, however, was surprised by her question and gaped at her, speechless and flustered.

“I’m her grandpa, Cyril Stanton.” Grandpa reached across the counter, shook her hand, and then gave me my candy bar.

“He lives at our house now. He gave me a nickel.” Grandpa’s rescue primed my pump, and I added the important details to Grandpa’s rather sparse introduction.

“Pleased to meet you, Mr. Stanton. I’m sure Harlan enjoys having you there.”

I clutched my candy bar in one hand and slipped the other back into Grandpa’s, pulling him out the door. I didn’t like sharing my time alone with Grandpa. I hung from his arm for our entire two block walk, waiting to open and eat the candy bar, an act that required two hands on my part, until I got home.

“Thanks, Grandpa.”

“You’re welcome, Jolene.” I smiled up at him, and his eyes smiled down at me beneath the black, bristly eyebrow so thick there was just one that went all the way across his face. I walked as slowly as possible, determined to eek as much pleasure as possible out of the short trip. I was convinced that heaven, at least the one described by my Sunday school teacher, couldn’t be much better than this.

Having Grandpa live with us seemed a heaven-sent solution when he first arrived. His diabetes had become more troublesome since Grandma Stanton died, but for years Grandpa continued to live and work alone in Nevada, Iowa, visiting our family often. When he went into insulin shock while driving one day, his car stalled on the railroad tracks. A swift rescue by the local police saved his life, but not his liberty or happiness. His driver’s license was revoked, and he was stranded. Living with us gave him places to go and people to see, and a way to get to both. For awhile the arrangement seemed like it would work. At age six, I thought life couldn’t get any better, but there was lots about adult life that I didn’t know.

I didn’t know that my grandpa who looked so young, with a full head of black hair barely flecked with grey, was going into diabetic shock often. My mother had to get up each night to check on him and correct the imbalance with an orange juice and sugar midnight cocktail. Even my sister knew the signs and gave him orange juice as needed during the day. I didn’t know that when school started in the fall, Mom was so tired from interrupted sleep that she could hardly drag herself to work. I didn’t know that my grandpa, who always acted so calm and caring and looked so dashing in the short sleeved sports shirts he wore unbuttoned at the neck, was losing his sense of judgement. I didn’t know that my grandpa, who gave us handpicked gifts like carved wooden wishing well banks from Canada and red felt cowboy hats with white trim as well as savings bonds for college, had kicked my misbehaving little brother one day. I didn’t know for many years that those were the reasons for my mother’s announcement one night.

“Grandpa Stanton isn’t going to live with us anymore,” Mom explained as we finished supper. “He’s going to live at an old folks’ home in Cedar Falls where there are nurses to take care of him and lots of people to talk to.” She tried to give it a good spin. “Grandpa even knows the director. He was the minister in Nevada when Grandma Stanton was still alive.”

I didn’t know that our minister had been so concerned about Grandpa’s situation that he had come to school, taken Mom out of class, and asked what he could do to assist her. I didn’t know that he had called the director of the Evangelical United Brethren (EUB) Home and made all the arrangements. All I knew was that I didn’t want this grandpa to leave, and I couldn’t imagine that my dad could want his dad to go.

We drove Grandpa to the home the day after Thanksgiving. Earlier in the week our minister had contacted the director of the home, effectively conveying the urgency of the situation.

“We have an opening right now, and we’ll hold it for Cyril,” the director and old friend agreed.

“The only thing is, he has to be able to walk in on his own.”

Mom knew Grandpa was failing fast, so as soon as the turkey leftovers were tucked in the refrigerator, she helped him pack, and the next morning we scrambled into the car. We were a pretty somber crew on the way over, but once we got there, from my vantage point, the old folks’ home was a great place to visit. Of course, I didn’t have to live there. A big statue of a lion stood outside the imposing front door of the many storied brick building that I was sure covered at least three city blocks. As honored grandchildren, we were allowed to climb on the lion and “ride” it. I took the honor very seriously and religiously performed my duty each time we went to see Grandpa.

Once we entered the building, scores of ancient eyes fixed upon us, wrinkled lips croaked greetings. “Look, Mabel,” I heard one starved voice marvel, “children.” Fluttery, shaking hands, moths to a flame, reached out to touch me as I walked by, and I shrank away, moving close to my father’s wheelchair. Sour smells, like the inside of my dad’s urinal, swirled around me, making my nose squinch shut and my mouth wrinkle.

“Jolene, get rid of that face. You’ll hurt their feelings,” Mom whispered.

I tried to smile, but every pungent, sharp breath twisted my face into a lemon. Our shoes clicked on the shiny floors of endless tomblike hallways until we stopped at the doorway of a small room. Grandpa put his luggage on the bed and unpacked. Once he was settled in, we stayed for dinner and visited awhile, gaining fortitude for our return trip which was over three hours tacked on to the three hours plus we’d spent getting here.

Our presence in the dining room presented a political problem. “Why,” one white-haired matron asked a dining room staff person, “do all three of those perfectly darling children get to sit at the same table? It is not fair.”

I searched the dining room, which I estimated was as big as a high school gymnasium, for the three “perfectly darling children”, but couldn’t find them.

“Jolene,” Mom asked, “would you be willing to go sit at the table with that lady?” She pointed to the outspoken matron. “She doesn’t get to eat with children very often. Try and get rid of that sour face and smile,” she advised. “John, you could go sit at that table with those nice men, and Jill, you can stay right there by Grandpa.”

Us? We were the “three perfectly darling children”? I was dumbstruck but willingly trotted over to the white-haired matron who was pulling an empty chair up close beside hers, motioning me over. “Well,” I wondered, “how’m I gonna act ‘perfectly darling’?” By the end of the meal, I was still clueless, but none of my tablemates seemed to mind. They just kept patting my head, offering to cut my meat, asking me questions, treating me as if I was “perfectly darling.” I was basking in the limelight, filled to the brim with the extra desserts they had passed on to me. “Whadda place to live,” I thought. “Grandpa’s got it made.”

Grandpa didn’t have it made. He was lonely, and we visited as often as we could, but the trip took a whole day, and even though we were “perfectly darling children” the moment we stepped into the old folks’ home, we were not always so on the trip there and back. Our first few visits chased away Grandpa’s loneliness, and our entrance into the dining room delighted him to no end.

“Look, Cyril’s darling grandchildren are here again” the cry would go up, and he chuckled as he watched the diners fight over us, the victors carrying us off as spoils to their table-length fiefdoms.

When we went outside for a walk with Grandpa, he handed us dimes. Yes, dimes. “Do you hear that bell?” He and Dad grinned. Mom steered Dad’s chair toward a bench where she and Grandpa sat down.

A magical tinkle of chimes drifted towards me. “What’s that?”

“The Good Humor Man,” Grandpa explained.

I looked blank. My dad was right beside me. Who else could be the “Good Humor Man?”

“The ice cream truck,” Dad translated.

“Oh.”

“Go on,” Grandpa coached. “Wave to the man and buy a treat.”

I obeyed and ran after my sister and brother to the truck. All the way home I tasted the ice cream bar Grandpa’s dime had bought.

I anticipated similar delights as we drove in the parking lot for our next visit, but they weren’t forthcoming. When we got to Grandpa’s room, I noticed his hair was still black, but he looked lots older. When we walked in to greet him, he didn’t look at any of us, just cocked his ear in the direction of the sound. His eyes were vacant, blinded by diabetes, and he couldn’t see how perfectly darling we looked that day. During the following visit we stood beside the bed where he lay unaware of our presence. By Thanksgiving, barely a year after he went into the home, he was dead.

I was too young to grieve, more than superficially, and so was my brother. Grandpa’s loss to me was a loss of creature comforts: unexpected dimes and nickels, a lap to sit upon, a smile that made me feel very loved, a hand to hold, a friend to talk to.

For my father and mother and sister, the grief was much deeper and wrenching. They had lost the one person who had time to give them the wholehearted emotional support they needed. My father and mother lost the last person who had shared their original vision of a hopeful future. My father, without brothers or sisters to comfort him, lost the most enduring link to his childhood.

While I had lost a bearer of sweet gifts, my father had lost his bearings.