by jphilo | Oct 21, 2014 | Reflections on the Past, Top Ten Tuesday

Last week’s top ten was about what I missed and appreciated about high school. This week’s list looks at the flip side of those high school coming-of-age years in the early 1970s.

10. Macrame anything.

9. The lack of air conditioning in August and May.

8. Listening to the really-love-your-peaches-want-to-shake-your-tree line from Steve Miller’s song, The Joker.

7. Learning while sitting rather than learning while doing.

6. Wondering about making it through high school and college, getting a good job, getting married, having a family, and every other adult rite-of-passage that scares high schoolers silly.

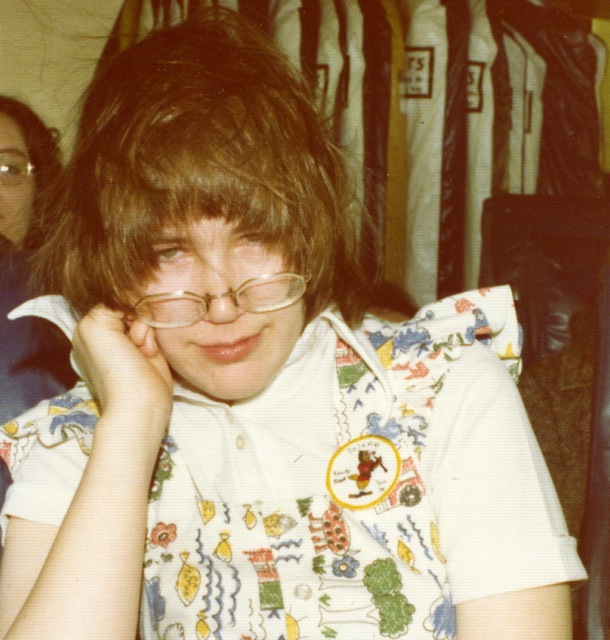

5. Daily insecurity about clothes, hair, shoes, and anything else a high school girl can be insecure about.

4. School lunches.

3. Gym class.

2. Zits.

1. Homework.

What don’t you miss about high school? Leave a comment.

by jphilo | Oct 14, 2014 | Reflections on the Past, Top Ten Tuesday

On last week’s road trip, I spent an evening with one of my best friends from high school. Every time we–or any of our high school crowd–get together, we remember why we were (and still are) good friends. And we remember and miss what was best about those fleeting and powerful years.

10. Throwing good luck pennies on the Pizza Hut roof.

9. Sitting in the stands and talking with friends during basketball and football games…and even watching the games now and then.

8. English and history classes.

7. Being part of a group that made sure everyone had a date for Homecoming, Twirp, and Prom.

6. The speech and drama teacher, Mr. Hallum, who demanded the best from his students and gave so much of his time to help them grow.

5. Looooong weekend band and speech trips on very uncomfortable school buses.

4. Marching and concert band during the school year and city band in the summer.

3. Church youth group and our leaders, Ron and Barb Ritchie.

2. Play rehearsals.

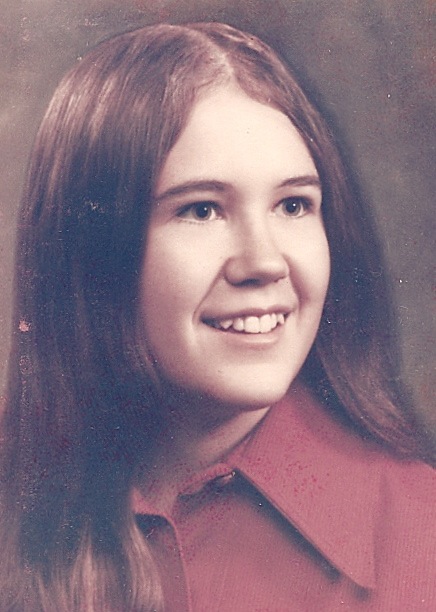

1. The best friends a person could ever have (in alphabetical order): Cheri, Jacki, Jane, Katie, Mary Anne, and Roxanne.

Okay, so what’s missing about what you miss about high school? Leave a comment.

by jphilo | Oct 13, 2014 | Family, Reflections on the Past

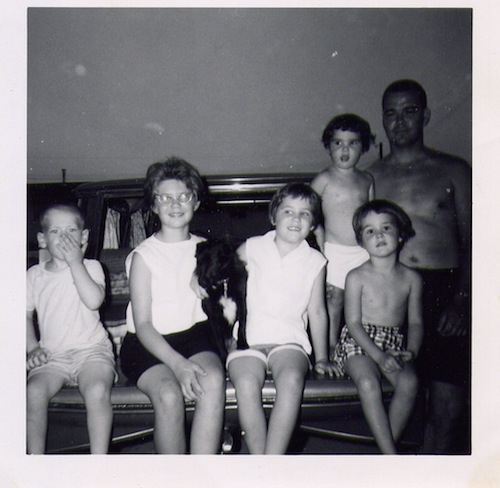

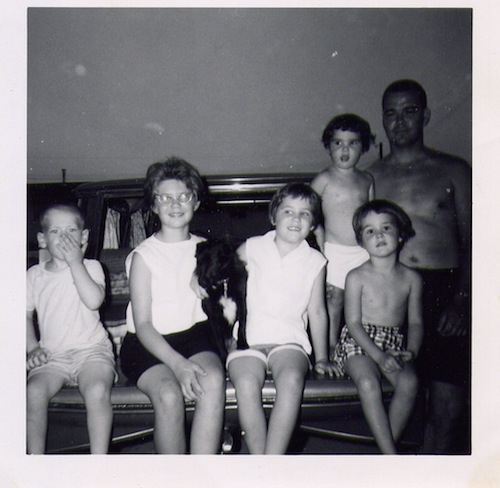

Had I been thinking straight way back in June, when I posted a chapter from Lessons from My Father, this would have been the chapter to start with. Now that I am thinking straight and you’re scratching your head about where my parents’ story began, the answer can be found below. Ladies and gentlemen, it’s my pleasure to introduce the bride and groom to you: Harlan and Dorothy Stratton.

The Perfect Picture

And he said,

Naked I came from my mother’s womb,

And naked I shall return there.

The Lord gave and the Lord has taken away.

Blessed be the name of the Lord.

Job 1: 21

“Hello, world, here I come!” he seems to shout from his wedding picture. His broad grin turns his cheeks into plump apples, the dress suit hanging awkwardly on his 250 pound frame. “I’m in here just to humor her,” the twinkle in his eye seems to say. “Just a few more pictures, and I’ll be knee deep in manure again.”

“How will I keep up with him?” her shy smile asks the camera. Wearing her sister’s wedding dress, she looks stylish and petite, but slightly out of place. Her hands, rendered large as a man’s by years of milking, are hidden by her bouquet, her muscular arms covered by bridal lace. “I’d rather be in the barn,” she whispers to the generations gazing at her face.

Exuberant and ready to embrace rural life in the 1950s, they faced the photographer’s camera with confidence. With a honeymoon highlighted by a Chicago Cubs game and a tour of the Chicago Stockyards, could they be anything but Midwestern farmers? A registered Shorthorn breeding business needed building when they returned. They were ready to live the dream they had planned and worked for since they had met in college three years before. They would farm in partnership with his parents, Cyril and Fern, a loving couple who doted upon their only child, my father. They would raise a family, a big family, with lots of kids to help on the farm and keep one another company. They were young, strong, talented, and willing to do all that was necessary to realize their dreams. It was June 3, 1951. Harlan and Dorothy Stratton had the pieces of their married life collected and ready to assemble into a wonderful picture. Over the next thirteen years, like a jigsaw puzzle in reverse, the pieces disappeared, snatched away until none remained.

The picture, at first, came together just as planned. My father and his father quickly built up a herd of Shorthorns. They were poised to provide quality stock to farmers all over the Midwest. My parents had their first child, Jill, in 1953, and she was the apple of her grandparents’ eyes. Then, Fern’s health took a turn for the worse, and everything changed. Her colon cancer progressed at an alarming pace, and the resulting medical bills threatened to devour the farm. Harlan and Cyril dissolved their farming partnership and sold their assets, so that both families were not ruined. That was in 1954. The first piece of the perfect picture was gone.

In 1955, the second piece was removed. Fern Stratton died of colon cancer after a long and agonizing struggle. She was fifty-five years old.

Life as farmers denied them, the couple decided to do the next best thing. Harlan would pursue a career in the Extension Service, through which he could stay close to agricultural life, rubbing elbows with the farmers who tended the fields and animals he loved. Harlan’s exuberance and skill made him a popular and effective county agent. He advanced rapidly in a career to which his personality, training, and experience were perfectly suited. He read voraciously, mostly about agriculture, his nearly photographic memory adding book knowledge to the practical experience he gained working throughout the county. He spent his days traveling the countryside, consulting with farmers about their crops and livestock, providing for them the latest research available from Iowa State University, a land grant college founded to assist the development of agriculture. His expertise with cattle brought him numerous opportunities to train farm kids in the art of showing cattle and made him a sought-after cattle judge at many county fairs.

Dorothy was a busy mother and housewife. She was content to support her husband, complementing his gregarious personality with her own shy competence. She enjoyed basking in the shadow of Harlan’s successes, dedicating herself to her family, which had grown to two when I was born in 1956. Whenever she had the chance, she took education classes at the nearby college. She wanted to complete her four-year teaching degree to become one of the first in her family to graduate from college. “Besides,” she told the housewives who questioned her drive to get her bachelors degree, “it’s a good thing to have, just in case I ever need it.”

Just as they settled into their new lives in Malvern, Iowa, where Dad was the new county extension agent, a doctor pulled away another piece of the puzzle in 1958. Harlan had ignored coordination problems and double vision that came and went for several years. When he couldn’t pass the vision screening for his driver’s license test, he finally went to the doctor. The diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and its rapid debilitating progress nearly robbed him of his will to live.

By 1960 few fragments of the picture remained. Harlan, now the father of two girls and one red-haired boy named John, couldn’t work anymore. He couldn’t show cattle. He couldn’t walk without assistance. He couldn’t drive, couldn’t write, couldn’t see well enough to read, couldn’t even tell if his bladder was full or empty. He was thirty-one years old.

By 1966 the last piece of the picture they thought would be their life together was snatched away. Harlan’s father, Cyril, died at age sixty-seven, his mind and body destroyed by diabetes.

Gone.

The whole picture was gone through no fault of their own. If any couple had a reason to be bitter, my parents did, especially my dad, one of the nicest guys you’d ever care to meet. This man did everything right…honored his parents, went to church every Sunday, played with his kids, worked hard, never said “Bah, humbug” at Christmas. Sure, he ate red meat, but he was a cattle farmer, and this was the 1950s. My mom was right up there with him in nice woman status…studied hard, was a dedicated school teacher, treated her in-laws like gold, rolled out pie crust at the county fair when she was nine months pregnant. Anybody who knew them would say, “They didn’t deserve this.”

So, did they become bitter? Did they tear up the wedding picture of the ignorant young couple so unaware of the pain awaiting them? I’m sure they wanted to, but they didn’t. Instead they looked at that wedding picture and noticed, hiding in the depths of my mother’s gaze and in the laugh lines on my father’s face, the beginnings of a second picture. This new picture was different from the one they had imagined, as tragic as the first one had been hopeful.

In my mother’s eyes glinted a determination to provide for her family, and inside her heart dwelt an extraordinary talent for teaching children, a potent combination that caused schools to snatch her up. In my father’s face were hidden laugh lines attached to invisible strings, pulling his face into a haunted grin, giving him an ability to face his family and the world with a smile, even when his mind was heavy with depression and loss. They stared at this new picture and saw themselves, not as innocent victims, but as confident victors. Over the years, they labored to piece together the new picture of their lives.

by jphilo | Sep 22, 2014 | Reflections on the Past

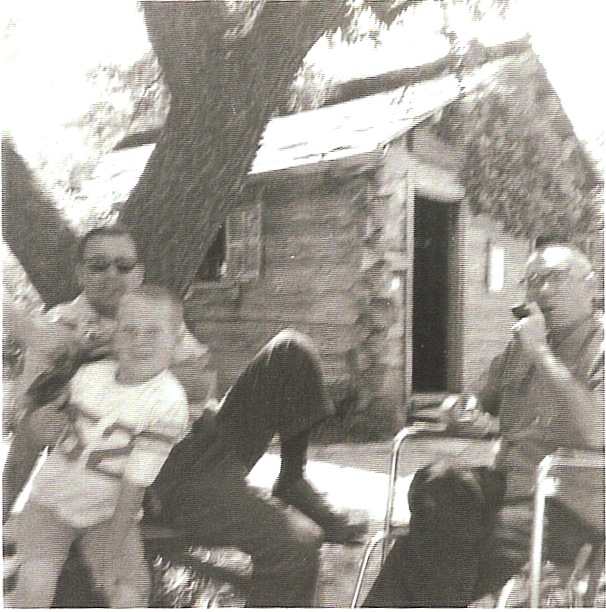

John, Jim, and Dad with the pipe that didn’t fall in the lake

The first half of Good Cheap Fun appeared on the Gravel Road way back in August. Today, you can finally read the second half of the excerpt from Lessons From My Father. As has been mentioned, this tale of vacation woe is packed with more catastrophe than a person can bear at one sitting. But if you want to risk it, Part 1 can be found here. And now, for the rest of the story…

At daybreak we slowly straggled into the kitchen, weary and welted, serious damage having been inflicted upon us during the night. Dad wheeled himself in. “Mornin’, everybody. Hope you all slept as well as I did. Wuddin’ it great to hear those cows mooin’ in the night?”

Despondent, nearly mutinous faces turned toward him.

Dorothy and Donna handed bowls around and placed boxes of cereal on the table. “What is that smell?” Mom asked, her eyes watering slightly. She sniffed me, then Julie, then Gail. “You all smell funny, like…”

“Like wet, ol’ mattresses full a dried pee,” Julie finished her sentence. “We’re real stinky.”

“Don’t worry,” Jim assured us. “We’ll be outside soon. There’s a real nice breeze. You can take soap and a washcloth into the lake when ya swim and get cleaned up. The good news is that the wind has skedaddled the mosquitoes, at least for now. Donna, where’s the key to the boathouse?” As Donna handed him the key, we slurped down our cereal, eager to witness the opening of the marine treasure trove.

We formed a merry caravan as we skipped our way across the yard. Dad, pushed by Jim, led the way, followed by six cavorting youngsters. The cavorting ended when John discovered the cattle had done more than just moo during the night. We picked our way daintily through their cunningly deposited land mines. Jim wheeled Dad to the shoreline near the boathouse, so he could supervise the water activities. Hastily, Jim braked the wheelchair while Dad pulled out his pipe and filled it. Dad was ready for the first smoke of the day, intent on enjoying the experience, enhanced as it was by the morning air, delicately laced with the aroma of fresh land mines.

Jim headed for the boathouse, key in hand. He inserted the lock and tried to turn it. Nothing happened. “Must be the wrong key,” he assured us. He headed back to the house to confer with Donna, but returned quickly. “It’s the right key. The lock must be a bit rusty. Why don’t you kids find a nice place to wade while I work on this a little?”

We wandered off. I spotted a particularly alluring bit of beach, overhung by leafy trees. The sun was getting hot, and the air was humid. I walked along the beach, heading for the shady spot. The sand turned to mud as I approached the shade. Enjoying the coolness, I waded back and forth, watching my feet stir up little muddy tornadoes under the water.

Eventually, the mosquitoes zeroed in on me, and I headed back up the beach where the others were waiting. I looked down and noticed blobs of mud clinging to my legs. I stepped in the water to wash them off, but they wouldn’t budge. I ran over to the others who were playing in the sand.

“Jill,” I said, “I can’t get this mud off my legs.” She bent down for a closer look.

“That’s not mud,” she informed me. “Those are leeches.” She reached down and took hold of one, pulling it out longer and longer, unable to break the powerful attachment between me and my blood-thirsty friend.

“EVERYBODY OUT’A THE WATER,” I screamed at the top of my lungs. “RUN FOR YOUR LIVES. THIS LAKE IS FULL’A LEECHES! GET OUT, GET OUT!” Then I ran, flailing and screaming, toward the house. “HELP, MOM, HELP! I GOT LEECHES ALL OVER ME! I’M GONNA DIE!” Being a child of slightly dramatic nature, I may have overreacted just a bit.

Mom came to the door with the salt shaker in hand. She had seen African Queen, so she knew what to do. Aunt Donna, looking only slightly less green than I felt, made a beeline down to the lake.

“Everybody, out,” she ordered. “This lake is full of leeches. You won’t be able to swim after all.” Groans and even tears greeted her announcement, but she held firm. “We don’t have enough salt,” she explained. “But,” she tried to comfort everyone, “you can still go out in the boats.”

They ran to the boathouse to check on Jim’s progress. There wasn’t any.

“This lock is rusted solid,” he explained. Everyone bent close to look. “Never seen anything like it. Guess we won’t be going boating.”

A wail of disappointment erupted. The noise made Mom and me look up from my mosquito-welted, leech-infested, salt-encrusted, pee-stinky little body. A movement caught my eye, and I noticed that Dad seemed to be inching toward the water as he savored his pipe. He seemed oblivious of his progress. I thought it was one of his jokes. “Mom, look at Dad,” I giggled.

Mom took one look at Dad, his wheelchair gaining momentum. She dropped the salt shaker along with my leg and shouted with more lung power than I knew she possessed, “Jim, Harlan’s rolling into the lake!”

Jim jumped up, hurdled over the children around him, and sprinted towards the rolling chair. He grabbed hold of the wheelchair just as the top of Dad’s boots were swallowed by the lake, and his knees stared the same wet demise right in the eye. Jim yanked him back to safety. Dad’s pipe, jerked from his hand by the force of backward motion, formed a perfect arc as it sailed out of his hand, and splashed into the lake.

“Dorothy,” he said, his humor seeping away as the specter of nicotine withdrawal approached, “I didn’t bring another pipe. Whaddya say we give it up’n go home?” Water dripped from his pant legs and boots.

I kept my hand on the salt shaker, my eyes alert for any sign of leeches beneath his socks.

“Yeah, let’s go home,” Jill chimed in. “We can’t get to the boats, and cuz of Jolene, we can’t go swimmin’.”

“Look at the sky, Jim,” Donna pointed out. “It looks like it could storm.” Sure enough, clouds were building up in the southwest sky. “We don’t even have a radio to check the weather, and this cabin doesn’t have a basement.”

Danelle, John’s age-mate and usually the heartiest and most countrified of our young crew, trudged towards us from the outhouse and solemnly announced, “I used up the last black and white page. The rest of you are gonna hafta to use color.”

We started packing.

As we lurched our way down the rutted lane, the wind rose and the clouds grew darker, forcing us to close the car windows. The humidity increased inside, enhancing the pungent odor emanating from our unwashed bodies. Jill actually enjoyed her little trysts with the cattle gates, as each encounter allowed her to breath untainted air. When we reached the gravel road, the adults stopped the cars and emerged gasping for fresh air. After a quick pow wow, they decided that rather than head all the way to Le Mars, they would drive to Pipestone, where we could be hosed down before spending the night with Grandma and Grandpa Hess. Taking a few last, deep breaths, they entered into the vehicles and drove at a rate I am guessing was more than a little above the speed limit.

We got to Pipestone in record time. Grandma was surprised to see us and after one whiff sent the children off in sets of three to the bathtub. “Use lots of soap and wash your hair,” she advised. She didn’t need to remind us to wipe with toilet paper and flush the stool when we were done. The pleasure was all ours. While we gloried in modern plumbing, the adults hung the sleeping bags on the line to air.

We emerged from the bathtub, clean and shining, wet-haired, and clothed in pajamas from Grandma’s famous pajama drawer, our own sleepwear enjoying a quick spin in the washing machine. After a blessedly mosquito-free supper, we discovered we were exhausted, with lack of sleep and disappointment bearing down upon our eyelids. Grandma made up beds for us on the furniture and on the floor and in the basement. We children hit the hay immediately, listening to the talk and the laughter drifting in from the breezeway as the adults recounted the events of the day.

Just as sleep claimed me, the phone rang. Hands shook me awake and urgent voices ordered me to hurry to the basement. “Tornado,” I heard someone say. I grabbed my pillow and blanket and headed for the basement, following the rest of the children. The adults came behind us, Jim and Mom bringing up the rear, as they took what seemed like an eternity to maneuver Dad and his wheelchair down the narrow stairs. Grandpa switched on the radio, and we listened to its nearly unintelligible crackle as we sat on the basement floor.

Dad surveyed the room, his eyes bright and his grin wide, if a bit forced, due to lack of nicotine. “Boy, I’m sure glad this vacation was free,” he said. “I’d hate to pay good money for a weekend like this.”

“Now, Harlan,” Mom begged, her eyes wet. “Don’t start.”

“Don’t start…what?” he demanded. Mom jerked a slight nod in the direction of Aunt Donna, who was blinking back tears.

“This weekend was supposed to be so fun,” Donna’s voice quavered. “Instead, it was a disaster.”

“At least we got out of the cabin before the tornado,” Jim comforted her. “We’re all safe and sound. And Harlan’s right, at least it was free.”

Dad cleared his throat and spoke again. “Well, not quite. Somebody owes me a pipe.”

We all began to laugh.

To this day, the Hoeys and the Strattons love to get together whenever we can, though we’ve learned to pay as we go. We’ve endured many adventures, but no other trip was as disaster-laden as our free weekend. That trip has become the measuring stick, the lodestone, the gauge to which all other disasters are compared. The truth of the matter is, while no other trip has been nearly so bad, no other trip ever provided as much laughter either. Dad did lose his pipe, but he gained a story that could make him laugh till he cried each time he told it.

“I sure hope,” he would end the story, “I sure hope there’s some dumb fish in that lake enjoyin’ a real good smoke.”

by jphilo | Aug 11, 2014 | Reflections on the Past

There’s just enough summer left for one more Lessons from my Father vacation story. This tale of vacation woe is packed with more catastrophe than a person can bear at one sitting. So this post contains the first half of the tale. Come back in about a month for the rest of the story.

Good, Cheap Fun

For indeed when we were with you,

we kept telling you in advance that we were going to suffer affliction;

and so it came to pass, as you know.

I Thessalonians 3: 4

“Head ‘em up, move ‘em out,” Uncle Jim crowed the words as the Stratton/Hoey party of ten crowded into two vehicles, ready to hit the road again. We were anticipating a weekend of pure enjoyment, two days of carefree existence, forty-eight hours of good, cheap fun. In fact, this adventure was cheaper than cheap. It was free.

An older couple in our church had told Aunt Donna about their lakeside cabin north of Willmar, Minnesota. They told her our families could use the cabin any weekend in the summer when they were not there.

“Dorothy, it’s free.” I could hear Donna’s excited voice in the kitchen. “Free! It’s a two-story cabin by a lake, with a private dock, and a boathouse stocked and ready for our use.”

“Donna, it sounds too good to be true. They don’t want us to pay anything?” Mom, a wise skeptic, knew there was no such thing as a free lunch.

“That’s what she said, Dorothy, absolutely free. They love to loan out their cabin to young families. Why they even gave me a guide book they’ve written up, pointing out sites of interest on the drive up.”

“Well, if you’re sure…”

“I’m sure. Grab your calendar. ”

Our weekend was scheduled and off we went, four adults and six active children ranging in age from three to twelve. We were ready for easy livin’, ready to catch our dinner in the well-stocked Lobster Lake, ready to dip those Minnesota walleye and northern pike in egg, roll ‘em in the cornmeal we’d brought along, ready to fry ‘em in the bacon grease stowed in the cooler which was packed in the trunk alongside our fishin’ gear, our swimming suits, and the picnic baskets. This weekend would be the stuff of memory, of legend, and it was free.

Jim drove the vehicle ahead of us while Dad kept him entertained. Neither made any effort to corral the three feisty children in the backseat. My mother drove our tan Plymouth at a safe distance behind the men’s car, my two traveling companions prospering under my loving and bossy care.

Eagerly, Donna read excerpts from the handwritten guide book while Dorothy steered us down the road. “As you travel north of La Verne, Minnesota, on Highway 75, keep looking west. You will see the Blue Mound Inn, a restaurant just recently established and quickly gaining a reputation as one of the area’s finest eateries.”

I swallowed my saliva as I looked out the window. Our car zoomed by the establishment; my hopes of a chance to sample the cuisine predictably dashed.

Anticipation of free lodging and food propelled our parents down the road that hot June day, and the detailed directions in the guide book led us from the state highway to a black-topped county road to a gravel road to a rusty mailbox guarding an overgrown and winding lane. The lane, rutted and narrow, led to a mangy grove, in the middle of which stood a derelict frame farmhouse, which at one time might have been painted white.

“According to the guide book, this has to be the lane. You will find a few cattle gates along the lane. Please shut the gates after you go through,” Donna read from the guide book again. “There’s a cattle gate, that’s for sure.” She peered down the dusky lane. “I guess the cabin must be between the old farmhouse and the lake.”

Both vehicles stopped, balking at the prospect of navigating the lane, which was doing a pretty good imitation of a miniature Grand Canyon. Donna hopped out to confer with Uncle Jim. He agreed, as Dad nodded approval, that indeed, the cabin must be on the far side of the old farmhouse. They assigned Jill, as oldest child, the honor of opening and shutting each gate along the way.

Donna got back into the Plymouth, and Dorothy and Jim drove carefully, avoiding the precarious ruts in the lane. Numerous halts, due to the countless gates, slowed our progress and left Jill cursing her dumb luck as oldest of our young generation. As our cars rounded the farmhouse, we were rewarded with a breath-taking view of the lake. We spied a boathouse and a fragile-looking dock, but the two-story cabin of our imaginations escaped detection. The farmhouse, however, did have two stories, the higher of the two listing a good six inches closer to the lake than did the lower one.

“You don’t suppose…” Mom’s unwelcome thought trailed off.

“No, this couldn’t be it.” Donna finished the thought. “We must have made a wrong turn. I’ll just go try the key before we head down that lane again.”

Donna marched to the screen door and yanked. It wouldn’t budge. She peered closer and spied a hook latching the door securely from the inside. A key was of little use here. Donna executed a neat about face and headed back to explain the situation.

“Lemme take a look,” Jim suggested. He went to the door and rattled the knob. It held firm. He examined the window near the door and worked a small section of its rusty screen loose. He managed to open the splintery window sash, but there was no way his body would fit through the small hole he had created. “Donna, send Julie-bug up here. She’s small enough to crawl through, I think.”

Julie, nearly overcome by the importance of her assignment, straightened her young shoulders, and walked solemnly to fulfill it. Uncle Jim lifted her and squeezed her through the opening, pulling back on the screen as she squirmed her way in. Julie opened the kitchen door and then unhooked the screen, emerging from within victorious. Donna put the key in the lock, sure it wouldn’t fit. Unfortunately, it did. The summer cabin of our dreams suddenly became a nightmare.

Donna walked through the door and, to her credit, did not faint as she surveyed the amenities of our free digs. My mother clung to consciousness also, which was good, as she was still at the wheel, parking the car in the least overgrown patch of lawn she could find. Uncle Jim managed a weak grin as he ran back to his car and pulled it in place beside her. Dad, taken aback by his first view of our palatial accommodations, began laughing so hard he couldn’t gasp out a snappy comment. We young ones, having waited patiently for at least five miles of the approximately 175 mile trip, could be patient no longer. We poured out of the car, falling over one another in our haste, ready to race to the lake.

“You kids be careful,” Mom yelled as she got out of the car. “Come back here for a minute.” Normally, we would have ignored her instructions and headed straight for the water, but the overgrown lawn impeded our progress, and the squadron of Kamikaze mosquitoes guarding the lake drove us back.

“Head for the house,” Jim barked the order, and we obeyed. We flew into the house and slammed the door, slapping at the enemy pilots invading the kitchen.

“I gotta go…bad!” John spit out a few mosquitoes as he spoke. He headed through the house on a whirlwind mission to locate the facilities. Seconds later, he returned to the kitchen with a puzzled and desperate look on his face. “I can’t find the bathroom.”

As he spoke, the door opened. Uncle Jim wheeled Dad in. A formation of fighter mosquitoes accompanied them. “Johny, the bathroom is outside. I spied the outhouse in the grove,” Dad said.

“An outhouse!” Mom exclaimed. “Donna, did you pack toilet paper?”

“No,” Donna’s voice wavered.

“Neither did I.”

As John danced painfully, Jim looked him in the eye. “John, be a man and be the first to test the facilities. Just pray for a Sears catalog. And don’t dawdle. The skeeters will carry you off if you aren’t careful.”

John pushed his way through the door and soldiered bravely through the yard to the outhouse leaning precariously in a shadowy corner of the grove. An honor guard of mosquitoes escorted him to his appointed task.

While John inspected the outbuildings, we girls completed a reconnaissance mission through the interior of the estate. We found a living room and dining room off the kitchen as well as one bedroom on the first floor. The bedroom held an iron bedstead, a greyish water-stained mattress stunningly setting off the set of rusty springs upon which it laid.

We tore up the stairs, oblivious of the wallpaper peeling off the ceilings and walls, dangling just above our little heads. We found three more bedrooms, the decorating motif of each strikingly similar to that of the main floor bedroom, although some mattresses were a tri-colored mix of grey water stains tastefully swirled among yellow urine patches and streaks of dried brown blood. Astute observers that we were, we noticed the musty odor pervading each room, amplified by the stifling temperature on the second floor. We paired up and wrestled open the warped sashes of the double-hung windows in each room, letting the cool, grass-scented evening air rush in. Then we headed down to the kitchen to report what we had discovered.

“Girls, that’s great,” Aunt Donna complimented us. “We’ll bring suitcases and sleeping bags in right after supper. Why don’t you all set the table while Dorothy and I mix up the tuna salad for sandwiches. One of you, grab the fly swatter and keep at the mosquitoes.”

With our expert help, supper was ready in a flash, and we all gathered hungrily at the kitchen table. After a remarkably short grace, punctuated by hands slapping at the dive bombers buzzing around us, we dug in.

“These bugs are getting worse,” exclaimed Donna. “Is the door shut all the way?”

“It sure is.” Jim got up to double check.

“Where in the world are they coming from?” Mom wondered. “Girls, was there a hole in one of the bedroom screens?”

“Nope,” Jill was positive.

“Are you sure, Jill?”

“‘Course I’m sure. I’m no baby.” She was indignant.

“How can you be so sure?” Dad took over the questioning.

Jill sat up very straight, swallowed one last mouthful of sandwich, slapped at the insect imbibing her life blood, then paused for dramatic effect. “I’m sure,” she intoned with great dignity, “cuz there were no screens.”

“No screens,” Mom echoed. She rushed out of the room and up the stairs, followed by Jim and Donna. Above us we heard window sashes banging down. Dad sat in his chair, trying to chew and laugh without spewing masticated tuna fish all over the table. He picked up his napkin and wiped the tears from his eyes.

The other adults returned to the room, clouds of buzzing biters creating an interesting halo effect around their heads.

“That takes care a that.” Jim broke the next bit of news gently. “Kids, the mosquitoes are just too thick out there tonight. We’ll have to hold off on swimmin’ ‘til tomorrow.”

We pleaded with him to no avail. The enemy agents circled outside the walls, and we were condemned to an evening inside our free summer cabin.

Putting a good face on it, Jim reasoned with us. “We’ll go to bed early, get up at the crack of dawn, and be in the boats all mornin’. Now, who’s gonna brave the outdoors and help me bring in the suitcases?” Outnumbered by merciless, winged warriors, we valiantly managed to unpack the cars in record time.

Sleep eluded us that night, trapped, as we were, in a war zone. Enemy agents conducted relentless attacks, engines buzzing overhead unceasingly. At some point in the night, cattle wandered into the yard. Their moos serenaded us, mingling with the aerial drills above us, driving away any hope of sleep. The upstairs bedrooms, with windows tightly shut, retained heat remarkably well. The hordes of fighter jets stirred the stuffy air not at all. We faced a conundrum. Should we throw off the heavy sleeping bags and leave ourselves vulnerable to enemy attack or burrow into the bags and die of overheating? Anxiously, we awaited the crack of dawn.

If you liked what you read, come back on September 15 for Part 2 of Good, Cheap Fun.

by jphilo | Jul 28, 2014 | Reflections on the Past

It’s summer, and for anglers that means it’s always time for fishing. My mother loved to fish, and her love of the sport took root in two of her three children. When you read this story about one of our family’s fishing excursions, you’ll wonder what possessed my sibs to touch a fishing pole again.

Gone Fishin’

When, therefore, Peter heard that it was the Lord,

he put his outer garments on, for he was stripped for working,

and threw himself into the sea.

John 21:7

“Careful, Jolene,” Mom warned as I crammed my bamboo fishing pole into the trunk. “Lay it in gently, or it will break.” I shoved it in harder, secretly hoping this bane of my existence would snap in two, so I could avoid the bullhead encounter I knew loomed dead ahead. “Jolene!” Mom grabbed the pole out of my hand and shooed me away. “I told you to be careful. Why don’t you get in the car and wait there?”

A golden opportunity to shape my own destiny was snatched out of my hands. I slumped my shoulders and dragged my saddle-shoe shod feet towards the crowded back seat.

“Come sit by me, Jolene,” cajoled Grandpa Stratton, patting the spot next to him. I climbed in and snuggled up to my grandpa, who had just enough room in his life for three grandchildren. With John on his lap and Jill and me on either side of him, we covered him with our wriggling devotion, knowing that he would divide his attention and the nickels in his pocket equally amongst us.

“Send Johnny up to the front, Dad. With four of you in the back seat, you’ll get mighty hot and crowded. It’s a good hour to Storm Lake, you know.” Dad reached up and cushioned John’s descent after Grandpa hoisted him over the seat back. “Turn around and sit down, John,” Dad ordered.

John delayed just a moment, crouching on the seat ahead of us, letting his ornery eyes peek over the car’s bench seat. He raised himself so his whole smirking face was revealed, baiting his practically perfect sisters. “I got gum,” he gurgled.

Jill and I refused to bite or chew upon this injustice, for sitting in the coveted positions next to Grandpa all the way to Storm Lake more than cancelled out the lure of a measly stick of gum. John sneakily bobbed his entire chest above the seat, exposing not one measly stick, but an entire package of Wrigley’s gum poking out of his front shirt pocket.

“Where’d ya get that?” I sputtered.

“Johnny, turn around and sit down.” Mom reiterated Dad’s order as she slid into place behind the wheel of the car. He flipped around and flopped down on the seat, in the process casting a triumphant look of glee at our incredulous, gapingly gumless mouths. We cuddled closer to Grandpa in a vain attempt of tit for tat, but it was too late. John was facing the front window, well aware that he had won the first round of the angler’s derby, dishing out to his sisters a particularly repugnant fish gumbo surprise.

The adults, unaware of the competitive undercurrents pulling their small fry to and fro, discussed the plans for the day. “Once we get to Storm Lake, the kids and I will get out our fishing poles and head for the dock. Harlan, you and Grandpa Stratton can sit in the car and visit or get out and sit on the shore.”

Grandpa lit Dad’s pipe and then his own Camel cigarette while Mom issued captain’s orders. “We’ll fish for awhile and then stop and eat the lunch I packed. I can hardly wait to try out my new rod and reel.” Mom’s excitement reminded us of how much she liked to fish, a pastime for which none of the rest of us had yet developed a similar passion.

“How come we kids don’t get a rod and reel? How come we gotta have bamboo ones?” Jill demanded. She was in her “everything should be perfectly fair” phase, a position I covertly admired, though I lacked her gumption in voicing such a potentially volatile manifesto.

“A rod and reel is for a grown up, Jill. Your bamboo poles are just fine while you learn how to fish.”

I knew what that meant. “A rod and reel was too expensive” is what that really meant. Lots of things were too expensive at our house, most notably, I fumed, whole packages of Wrigley’s gum. Jealousy, that green worm, writhed beneath the surface of my emotions, proximity to Grandpa unable to suffocate its parasitic presence.

“How’d,” I wondered, “how’d my brother get a whole pack a gum?” This day was going from bad to worse, so far as I was concerned. John had all the gum, Jill had Grandpa’s arm around her while the one at my side maneuvered his cigarette back and forth. All I had for consolation was the prospect of a hot afternoon spent spearing worm halves on a hook and drowning them in clear, cool water. The closer we drew to our destination, the deeper I wallowed in my misery. At the same time I could see anticipation rising in my mother as she sped towards an afternoon of fishing, indulging in a relaxation that seldom fit into her duty-filled days.

“Here we are,” she trilled as we pulled into the graveled parking lot next to the public dock. “Hmm, there’s not much shade,” she noticed and turned toward Dad and Grandpa. “I hope you don’t get too hot.”

“Don’t worry about me,” Dad assured her. He loved to bake in the heat, for he often complained that the numbness in his limbs made them, especially his legs, feel cold. “Maybe I’ll finally warm up.”

Mom didn’t hear a word he said, so intent was she on unpacking the trunk. She pulled out the poles and carefully leaned them against the side of the car. Then, she heaved the collapsed wheelchair out of the trunk, unfolded it, and set it out upon the gravel.

“Harlan, have Cyril push the chair up to the side of the car if you want to get out for awhile, but for Pete’s sake, don’t get too close to the water,” she warned him. She turned back to the trunk, searching for the fish bucket and the can of worms hiding behind the box containing our lunch.

Taking advantage of her unusually distracted state, the three of us oozed out of the car and inched towards the water, its cool wet promise drawing us to its inviting depths. “You kids stay out of the water!” Mom hollered, her head hidden in the trunk. “I told you no swimming or wading today, just fishing.”

“Mom,” we whined in hot protest, “we’re burnin’ up. We’re dyin’!”

“Do not go in the water.” She drowned our protests in a sea of commands. “Come get your poles. Jill, carry the fish bucket, and Jolene, you carry the can of worms.”

“Ewwww, I hate worms,” I squealed. “They make me barf.”

“Fine, John, carry the worms.”

Shooting a disdainful, manly glance my way, he picked up the can and strode down the dock, following Jill. The top of the entire package of gum waving from the pocket of the shirt which covered his puffed up little chest taunted me.

“Enjoy yourselves,” she sang out to the men in the car, swinging into line along the pier.

I lifted my pole and shuffled along, making steady if unenthusiastic progress until I managed to wrap my ankle in the fish line, nearly impaling my digits upon the fish hook in a vain attempt to untangle the situation. Coordination was never my strong suit. Knocking myself off balance as I swerved to save Thumbkin, I screamed, “Mom, HELP!” teetering precariously near the dock’s edge.

Mom turned and sprang into action. She dropped her rod and reel and sped towards me, pulling me to the middle of what I now considered the dangerously narrow dock. “Jolene, how did you do this?” She sat me down on the wooden slats and unwound the line from my ankle.

“I da’ know,” I sniveled. “Mom, will ya put the worm on my hook?”

Sensing another catastrophe in the making unless she agreed, she answered, “Yes, I’ll bait your hook.”

“Will ya take the bullheads off, too?” I pressed my advantage, for the nasty stingers behind their evil gills filled my cowardly heart and dainty fingers with dread.

“Yes,” she sighed, slight frustration tinging her voice.

I jumped up and bragged mightily as I headed to my fellow spawn, “Mom’s gonna’ bait my hook and take off the bullheads for me.” Round two of the fishing derby had ended in my favor.

“No fair,” they protested. “Mom!”

“Okay, Okay.” She swam into the fray. “I’ll help you all. Hold out your poles.” Patiently she baited our hooks and helped us cast our lines into the glassy water. She told us to watch the red and white bobber on the surface. “If it moves, you’ve got a bite.”

We sat on the dock, our feet dangling over the edge, tantalizingly close to the lake’s cool wetness. She baited her own hook, cast with expert precision and settled herself on the dock. Her shoulders relaxed and her eyes closed for a moment as she savored this bit of peace.

“Jolene, look.” Jill pointed at my bobber. “You gotta bite.”

“Mom, Mom, I gotta bite.” Never a rock in times of crisis, I nearly dropped the pole.

Her eyes popped open. “Hang on and pull it in.”

“What? How?” Overwhelmed by responsibility, my hands trembled and my muscles turned to mush. “Help!” I wailed.

“Good grief, Jolene, do you have to make everything into such a production?” Her firm hands covered mine, and with a mighty yank she lifted pole, line, and daughter skyward. A bullhead dangled at the end of the line, while a youngster hung suspended upon a length of bending bamboo.

“Help!” I bellowed.

“Sit down and shut up,” Mom commanded, and I did, at least until the bullhead flopped beside me on the dock.

“I’m not takin’ that off the hook. It’ll sting me.” Hysteria ratcheted my voice up a few notches from its already considerable volume. “Get it away from me, quick!” My arms and legs flailed as I inched away from the scaly monster.

“Jolene, shut up.” Jill put her head close to mine. “Everyone on this entire lake is lookin’ at you. You’re so embarrassing.”

I looked around and discovered that, indeed, my performance was gathering a nice little audience. The men in the rowboat were laughing heartily, and the fisherman on the shore to the right of the dock was shaking his head. My father and grandpa had left the car and were nearing the water’s edge, curious about the cause of the commotion.

“Look, Mom.” I pointed towards them, pleased that my antics were drawing such a crowd. “Dad and Grandpa are gettin’ in the water.”

Her rod and reel clattered to the dock again, and she sprinted toward the men. “That woman can run,” I marveled.

“Harlan, put on your brakes! You’re rolling towards the water!”

Harlan looked up, and then down, in surprise, and seeing that his wife was correct, braked just in time to avoid baptism by immersion.

“Cyril!” she cried as Grandpa stumbled over a piece of gravel in his attempt to catch the wheelchair. “Watch out!”

He reached forward and caught hold of Dad’s wheelchair just before his own unintentional proclamation of faith was accomplished.

“What are you two doing down here so close to the lake?” she scolded. “Would you please go back to the car, so I don’t have to worry about you two and the kids?” she begged.

“Dorothy, it’s gettin’ hot in the car,” Dad protested.

“Leave all the doors open,” she snapped.

“Let’s go back to the car,” Grandpa advised catching sight of the wild look in his daughter-in-law’s eye.

“My gum!” A shout from the dock wafted to the shore. “My gum fell in the lake!” John wailed and gnashed his teeth.

Jill and I stood frozen, watching the entire pack of gum float upon the surface of the water. Then we sprang into action flopping on our stomachs and reaching for the sweet, minty treasure, determined to rescue the five sticks of pleasure from a soggy fate.

John saw immediately that our arms were too short, took a deep breath, and bellowed, “My gum!!!!”

We grabbed our poles and tried to guide the waterlogged package closer, but to no avail.

A man of action if not forethought, John took the only step possible, one long step off a short plank, and splashed into the water.

“John, you can’t swim!” Jill informed him at the top of her lungs.

“My gum,” he burbled. His logic seemed impeccable to me. The gum was definitely worth the risk.

“Girls, get out of the way.” Mom barreled down the dock, her short legs moving faster than I thought possible. We got out of the way. She lay down on her stomach, inching as far out on the dock as she could safely extend, stretching out her arm. “John, grab my arm.”

“MY GUM!!”

“I’ll give you another piece of gum,” she promised. His arm swung toward her hand, and she strained forward, grabbing his wet hand, pulling him to her. She grabbed his collar, and by some reservoir of brute strength deep within herself, hauled him onto the dock. She sat a few moments, her chest heaving, her eyes closed, John dripping all over her lap.

After a moment, she collected herself and stood, steadying John on his watery feet. She looked at Jill and me. “Girls, pick up the poles. We’re going home.” Her shoulders sagged as she stooped down and picked up the fishing bucket, placing the full can of worms in its empty depths. She had lost round three of the fishing derby, but nobody had won.

She walked towards the shore, and we tagged along behind her, John, then Jill, then me.

“Mom,” John piped up, “when am I gettin’ my gum? You promised.”

We never went fishing again.