by jphilo | Aug 4, 2011 | Reviews

One Saturday in June, probably while cleaning bathrooms, I listened to an NPR interview with a young author. A young college grad had written a memoir about the 3,218 day reading streak she and her dad had racked up – an accomplishment that began when Alice was in fourth grade – and her dad promised to read to her for 15 minutes each night for 100 days in a row.

That’s a book I’d like to read some day, I thought.

Ozma’s book was on display at our library a few weeks ago, and I wasted no time in checking it out. The book was a delight to read. But then, how could a book about a dad and his daughter reading together every night from fourth grade to the night before her freshman year in college not be a delight? Ozma’s father went to great lengths to keep the streak going – like interrupting her play practice before midnight and squeezing in their read before her date picked her up for the senior prom.

But the book was much more than a recounting of how they made time to read or a list of what they read. The book is the story of how reading bound Alice and her father, a most remarkable elementary school librarian, together through good and bad times.

Through the end of her parents’ marriage.

Through the awkwardness of a single dad parenting his daughter during puberty.

Through separation from an older sister who went abroad for several months.

Through her father’s fight with the school board about the importance of reading to kids.

And so much more.

This book is not long or scholarly or deep. It is not hard to read. But, as our local librarian said as she checked it out on my card, it’s a book that will make you want to read to your children. Which means it is a very important book for parents and grandparents and teachers and book lovers everywhere. And Ozma has a website with book lists and suggestions about how to start a reading streak with the kids in your life.

But read the book before you visit the website. Just do it. You (and your kids) will be glad you did.

by jphilo | Jun 24, 2011 | Reviews

Whew, I finished reading Catch-22 last night and am finally done broadening my cultural horizons for the summer. A couple weeks ago, I posted my current reading list and mentioned that Joseph Heller’s WWII novel hadn’t captured my interest. Still, I slogged on, determined to finish the modern classic with the title that’s become an American idiom for no win situations, double binds, and hamster wheel thinking.

I hoped it would grow on me. But it didn’t. The book’s satirical look at the ending months of WWII in Italy read like an unedited MASH rerun. Of course, the implications of that comparison are entirely unfair because the book came out long before MASH. In fact Catch-22 may have planted the idea for MASH in the heads of its creators. And I’m pretty sure the book was required reading for the writers and actors who were part of the movie and TV series.

But this review is about Catch-22, not MASH. So I’m trying to imagine the effect the book had when it was published in 1961. It’s irreverent tone, non-chronological progression, and jaded view of military leadership would have been a threat to the straight-laced American populace in those days. For veterans of WWII, it must have been a slap in the face. But to those watching the Viet Nam War progress, it was a prophetic indictment of unfolding events. For the young men sent to Viet Nam, it spoke truth.

So, by virtue of timing and novelty and skilled satirical writing (though I didn’t enjoy the book, I did admire the writing), it became a classic often assigned in high school English classes. (But not at my high school, where the English teachers were WWII vets.) And the thought of teenagers reading the book bothers me, because the message – the absurdity of men, the randomness of chance, the hopelessness of life – is a disturbing one. It’s a book I’d want to know my kids were reading so we could discuss it together. Which makes me wonder. Did my kids read it in high school? Have they read it since? What did they think of it?

And how about you? Have you read Catch-22? What’s your take on it? What effect has it

by jphilo | Apr 22, 2011 | Reviews

The graduation announcements have been rolling in this week, along with RSVPs for the Time Capsule Opening for my final class of fourth graders, now high school seniors. So my mind’s been running through memories of our year together, recalling their 9 and 10-year-old faces, remembering the hopes and dreams they shared in their writing or in our whispered conversations in the hall or at my desk.

Those memories put me in the right frame of mind to read The Tale of Despereaux, a children’s chapter book recommended by my daughter and new son. (They are young adults who have already discovered a great truth – quality children’s books are some of the best literature around.) “You should read it,” they agreed. “It’s wonderful.”

Of course, they were right. This lovely tale of a tiny mouse with very big ears and a brave heart, written by Kate DiCamillo who also wrote Because of Wynn Dixie, is wonderful. It contains all the necessary fairy tale ingredients:

- an unlikely hero – the mouse described above facing an impossible task

- an dead queen – who died in her soup

- an stupid king – who despite his stupidity loves his wife and daughter with a pure heart

- an beautiful princess – of modern Disney quality, resourceful and spunky

- a blundering sidekick – a poor, ugly peasant girl with dreams of being a princess

- peasants with hearts of gold – a cook and a gruff jailer

- an evil villain – in this case, a highly despicable rat

DiCamillo combines those ingredients with love, red thread, cauliflower ears, a dungeon, a French mouse who wears too much make up, and the outlawing of everything soup – kettles, bowls, spoons, and broth – to serve up a tale that will warm the hearts of readers from ages 9 to 90. By the end of the story, the lives of young readers are enriched by the acquisition of a worthy fictional role model, the belief that some things are worth great sacrifice, and an expanded vocabulary, thanks to a story sprinkled with words glorious, but unfamiliar to most 9-year-olds.

The expanded vocabulary bit is enough to make a former elementary teacher’s heart beat a little faster. But what really got my heart beating was imagining reading The Tale of Despereaux aloud (and this is a book meant to be read aloud) to fourth graders. I could see the earnest eyes of little boys shining, as in their minds they became the tiny, heroic mouse, risking life and limb for good and truth and honor. I could see timid, young girls sitting up straighter as they started solving their own problems and showing compassion to those in need. For the first time in a long time, I was reminded of the power of story in the lives of children. For the first time in a long time, I missed my classroom. Only a powerful book could evoke such a response.

Kate DiCamillo’s The Tale of Despereaux is one powerful book. Simply put, it’s wonderful.

by jphilo | Feb 25, 2011 | Reviews

I don’t often go out on a limb to recommend a book before finishing it. But today, after listening to a quarter of My Reading Life, narrated by it’s author, I give it two thumbs up. As a mom, a teacher, an avid reader, a writer, and too broke to take a long vacation this year, My Reading Life resonates with me. Here’s what I like so far:

- Conroy’s loving tribute to his mother paints the picture of an extraordinary woman. She wasn’t able to attend college, but furthered her education by reading constantly. She taught him to love books, and their family’s story shows the great influence parents have on their children’s reading lives.

- His English teacher also profoundly influenced Conroy’s career choice and evolved into a life long friendship. For tired, discouraged teachers who doubt the difference they can make in the lives of young people, this real life story will restore hope. I’ve been out of teaching for seven years now, and Conroy’s words reminded me of the nobility inherent in serving children.

- Conroy’s love of literature, words, and writing echoes my own leanings. After an entire lifetime of being considered strange for preferring reading and savoring beautiful words over recess, gym class, Girl Scout hikes, kick ball, horse back riding, and other non-verbal pursuits, I have discovered a kindred spirit.

- He has read widely and drops titles like flower petals on the pages. The bad news is that my reading list is getting longer with each chapter read. The good news is that the stack of books on my nightstand will soon glitter with tried and tested literary gems.

- This memoir makes me want to read more of Conroy’s work. So far, South of Broad has been my only foray into his world, but it won’t be my last. With the price of gas rising daily, reading my way through his novels this summer will be an affordable journey south.

Unless something changes on the way through the remaining two-thirds of A Reading Life, this audio rendition will compel the ownership of a print copy. Like Madeleine L’Engle’s Walking on Water, this book demands the underlining of key phrases, Post-it flags to mark passages that resonate, exclamation marks in the margins, and a list of must-read books gleaned from its pages and jotted down on the inside front cover. So when I finish listening to My Reading Life, I will give it the active rereading it deserves, something I don’t have time for very often these days.

In my book, that’s the highest compliment there is.

by jphilo | Feb 24, 2011 | Reviews

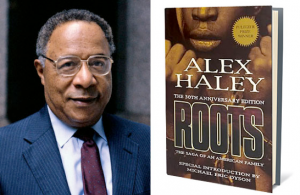

Roots, Alex Haley’s ground-breaking novel was first released in 1976. The saga of an Kunte Kinte, an African abducted by slave traders and shipped to North America, and his descendants made a big splash at the small pond midwestern college I was attending. I read the book avidly, deeply disturbed by the chronicling of one of the most immoral aspects of our country’s history. The description of the captured men’s treatment on the slave ship is one of those haunting literary pictures, along with the final scene in Grapes of Wrath, permanently etched in my mind.

By the time the TV miniseries aired in 1979, Hiram and I were married. We, along with most Americans, tuned in for the new and exciting form of entertainment. The producers touted LaVar Burton, a relative newcomer, as the star, but Ben Vereen’s performance as Chicken George is the one I remember most vividly.

For the past few weeks, while listening to the 30th Anniversary Audio Performance of Roots, those thirty-year-old memories came tumbling into my consciousness again. Kunte Kinte and Belle, their daughter Kizzie, her son Chicken George and his wife Matilda, one of their sons Tom Lee and his family, all come to life against the backdrop of Haley’s meticulous recreation of African and American history stretching from pre-Revolutionary War times to post-Civil War days.

Though much of Haley’s research and some of his genealogical claims have been discredited since Roots was first released, the essence of the book still rings true thirty years later. The depiction of the cruel and demeaning institution of slavery has lost none of its horror. The corrupting and pervasive effect power can have on those who hold it is as terrifying as ever. And evil’s inability to completely snuff out hope in the hearts of the oppressed is the miracle and message readers can cling to.

If you seen the miniseries, but haven’t read Roots, you should. The book has many details and nuances the series didn’t have time to capture. If you’ve read the book, maybe it’s time to check out the audio version and give it a listen. So far as watching the miniseries goes, maybe it would be a good way to wile away the hours when the next blizzard hits. By the time you finish watching, it might be spring!

by jphilo | Feb 18, 2011 | Reviews

When teachers or former students and their parents ask if I miss teaching, my answer often disappoints them. After twenty-five years of rigid schedules, grading, report cards, school politics, recess duty, teacher evaluations, curriculum writing, and inhaling every virus trapped in stale, classroom air, it was time for a new adventure.

But, there are a few things I miss – creating a community of trust in the classroom, being allowed into a nine-year-old’s world, and reassuring parents of a child’s worth and ability. I also miss staying abreast of developments in the rich world of children and young literature. That’s hard to do without the recommendations of a classroom full of kids and the school librarian to point me to the best and brightest new writing each year.

Once the first draft of my new book was complete, the itch to read kid and young adult lit began. But I didn’t know where to start until my friend Katie Wetherbee of Key Ministries suggested The Wednesday Wars.

“It’s fantastic,” she said. “You have to read it,” she said. So I did. And she was right.

The book is a gem, which is no surprise to those who follow it’s author, Gary Schmidt. He’s written three other books, Anson’s Way, Straw Into Gold, and Lizzie Bright and the Buckminster Boy, a Newberry Honor Book. After reading The Wednesday Wars, they’re all on my must read list.

Why? Because Schmidt wove a rich tapestry from the staples of middle childhood – friendship, rejection, school, baseball, cynical older sisters, teachers, parents, the realizations that adults are frail humans and that all issues are not black and white – and the unexpected elements of Shakespeare, pet rats, cream puffs, cross country running, and architecture. He deftly fit unlikely components together, thanks to generous amounts of humor and a realistic 1967 story world, complete with an appearance by Mickey Mantle and news reports about Viet Nam, the deaths of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy.

Revealing more about the plot would ruin the story for those of you who haven’t read it. Instead, meet two of the main characters. The first is seventh grade nerd, Holling Hoodhood. With a name like that, could he not be a nerd? The second is Mrs. Baker, a precise and demanding teacher. She is also Holling’s nemesis in his Wednesday afternoon wars.

For fear of spoiling the fun and the poignancy of The Wednesday Wars, I won’t say anymore. Except for this. Thank you, Katie Wetherbee, for recommending The Wednesday Wars.