by jphilo | Jul 11, 2014 | Reflections on the Past

Summer is vacation time for many families. Today’s excerpt from Lessons from my Father describes summer travel trips, which our family took, due in large part to the kindness of my mother’s sister, Donna, and her husband Jim.

Lifesavers

This is true and undefiled religion

in the sight of our God and Father,

to visit widows and orphans in their distress…

James 1: 27a

The blue station wagon was full to bursting as it sped south down Highway 75. Jim, my high school social studies teacher-uncle, was at the wheel. He was so dark-haired and tanned that Mom’s crazy Uncle Bob swore Jim was Japanese. “He’s dark, he’s short, last name like Hoey…gotta be a Jap,” Bob growled every time he saw my handsome uncle.

My father, urinal at his feet, arm resting out the open window, provided a steady stream of small talk, guaranteed to keep Uncle Jim alert and entertained. Cousin Julie, age three, sat between them, her eyes on the road ahead of her in a valiant effort to keep her car sickness under control.

Mom sat in the back seat with her younger sister and Uncle Jim’s wife, my aunt Donna. Donna’s hair was black to Mom’s brown, her eyes brown to Mom’s blue, and she was a good four inches taller than her vertically challenged sister. For all that, you could tell they were sisters and elementary teachers to boot as they masterfully kept in line the crowd of children in the cargo bay behind them.

Crowded in the bay, along with luggage for ten people and the paper grocery sacks and cooler full of food for our traveling meals, were any combination of the four other children: Jill (11), Jolene (8), John (5), Danelle (5), and Gail (4). One of the children, whichever one had most recently been caught misbehaving, sat, bored and restless, between the two terrible sisters, while the other offspring cavorted noisily.

Jill, conscious of the elevated rank her advanced age provided, held court among us. She explained to us the mysteries of childhood, including why Aunt Donna insisted we line the toilet seats in the filling station bathrooms with toilet paper before sitting. “You can get diseases otherwise.” Too frightened to ask what those diseases might be or how toilet paper might fend them off, we kept Mr. Whipple in business for years. When Jill’s wisdom ran dry, Danelle, oldest of the Hoey brood, showed us how we could rearrange the luggage on the return trip so there would be room for the dog, the two cats, three lizards, and the live clam collection she knew her parents would allow her to take home.

We entertained one another for hours, telling Gail of the three-horned-cows we saw out our side of the car. She would scramble over to look, and we would hide her coloring book. Once she found it and settled down, we commented on the grasshoppers so big and fast they were passing the station wagon. She’d take a look and discover her coloring book gone missing again. We babied little Julie, dragging her back with us when her car sickness subsided and dumping her into the front seat when she looked green around the gills.

“I’m hungry,” I intoned as I struck my most dramatic starvation pose. “When do we eat?”

“Anybody else hungry?” Mom asked.

“I am.”

“I’m starving.”

“I have to go to the bathroom.”

“Jim, the kids are hungry. Isn’t there a roadside park coming up soon?” Donna added, “I think it has a bathroom, too.”

“I see a McDonald’s.” Danelle, the eternal optimist, made a gallant attempt at picnic insurrection. “We could eat there.”

“Too expensive,” Donna and Dorothy chimed in unison, another facet of their family resemblance surfacing.

“We’ll stop at the park and eat.” Jim squashed the insurrection with the turn of the steering wheel. “What kind of sandwiches, Donna?”

“Bologna on white bread with mayonnaise and butter. Plus, we have bananas, potato chips, water, and cookies.”

“My favorites,” Dad licked his lips.

We arrived at the park and checked out the playground equipment while the grownups set out the picnic. We swarmed around the food like bees to honey. “Wait a second,” Jim commanded as our hands reached for the white bread and bologna. “Harlan, would you say grace?”

“Certainly,” Dad assented.

We hunkered down for a long wait.

“Would you all please bow your heads and fold your hands?” Dad waited until we were properly positioned. “Our gracious Lord and blessed heavenly Father, we thank you today for the food set before us by the loving hands that prepared it. We thank you, too, for this opportunity for fellowship together.”

I opened an eye to see if Dad was winding down. When I saw him take another deep breath, I bowed my head, sighed, and squeezed my eyes shut.

He was just getting warmed up. “Thank you, also, for the bountiful precipitation you provided in northwest Iowa in the form of one point five inches of gentle, soaking rain last night. We pray that you extend such a blessing to all the farmers, that they can enjoy a bumper crop in the upcoming harvest season.”

I yawned loudly.

Dad ignored the hint. “We ask, too, that you continue the weather pattern of hot daytime temperatures, warm evenings, and high humidity so conducive to proper crop development at this crucial time in the lives of those who work the soil.”

I peeked again in time to see Gail faint from hunger as Mom elbowed Dad’s arm. This time, he got the hint and hastily concluded, “In the name of Jesus Christ, Your Son. Amen.”

We dove for the Wonderbread. In less time than it took to bless the food, we inhaled our meal and headed off to the swings, leaving the adults in our wake to enjoy a more leisurely repast. Twenty minutes later, our parents squeezed us back into the vehicle, shut the doors, and we headed down the open road.

“I gotta go to the bathroom,” Gail announced two miles later.

“We were just at the park. Why didn’t you use the bathroom there?” an exasperated Donna asked.

“It wasn’t a bathroom. It was an outhouse…gross. And it didn’t have any toilet paper.”

Gail summed it up pretty neatly, I thought.

“Jim, Gail has to go to the bathroom.”

“So do I.”

“So do I.”

“Me, too.”

“Just a few more miles to the next town,” Mom assured us. Five towns later, after innumerable pleas and dire warnings of imminent bodily function catastrophes, Jim put on the brakes and headed for the blessed Texaco star.

Filling station attendants from Iowa to Kansas stared open mouthed, too amazed to complete the back flips their TV commercials promised, whenever Jim pulled up to the pump. He parked the car, and the doors opened to pour out upon the pavement an endless stream of youngsters.

“Stop, hold on!” Dad bellowed in a voice sure to be heard all the way to Kansas and over the rainbow. “One of you kids come back and get this.” He held up the black leather bag which held his urinal. “Take what’s inside and rinse it out good,” he said with a wink, the very soul of discretion. While the rest of the family visited the facilities, he turned his attention to the attendant, who was staring in a state of shock at the trail of children heading to the bathrooms, and continued with him the conversation Jim’s call of nature had interrupted.

As the tank filled, the attendant proceeded to wash every window in the low riding station wagon. As he worked his way to the back of the vehicle, he came face to face with another nasty shock. Tied to the top of the car was Dad’s wheelchair, wheels spinning in the wind.

“That’s mine,” Dad explained.

“Don’t say,” muttered the attendant.

“Couldn’t fit it in the back,” Dad went on. “Too many kids.”

“I’ll say,” the attendant agreed. “Looks pretty crowded in there. Where ya headed?”

“Dearing, Kansas. That’s where my brother-in-law is from. Going to visit his folks, see the country.”

“Don’t say,” marveled the attendant. “Have a good trip.” At that point, the sparkling conversation ended and a horde of children ran back to the car.

“Mom, I wanna sit in front!” John hollered, his volume nearly matching his father’s. “I’m tired of all them girls.”

“‘Sright, John. Get up front here with the men,” Uncle Jim agreed, his Kansas twang growing stronger as we neared his home state. “Julie can sit in the back seat as long as there’s a bread sack handy.”

John grinned, glowing with pleasure as he joined the men.

The girl children piled into the back seat and scrambled into the cargo bay. Donna, Mom, and Julie took up residence in the back seat, and we took off, the wheels of the chair on top of the car gaining speed as Jim’s foot pressed the accelerator. The man with the Texaco star stared at us, mouth slightly ajar, as we aimed for the highway. He looked like he didn’t know what had hit him. The Stratton/Hoey gang had that effect on people, all the way to Kansas.

The Stratton/Hoey gang had that effect whenever they traveled together, and they traveled together plenty, as long as Dad was able to go along….Ponca, Nebraska; Springfield, Illinois; Pipestone, Minnesota; Sioux Falls, South Dakota; Grand Rapids, Minnesota….why travel alone when it was cheaper by the dozen? Our numbers approached that dozen marker, when eight years after Julie, the Hoeys produced their youngest, a son named Dan, and eased John’s burden of being the token male cousin.

Jim must have known that his presence allowed Dad to visit places beyond his limited horizons. He listened to Dad’s innumerable stories. He hoisted Dad’s wheelchair to the top of the station wagon, tied it in place, and reversed the process as needed without complaint. He gently lifted Dad from car to wheelchair to toilet seat to wheelchair to car. He pushed the wheelchair up paths that even Mom could not negotiate, holding open a few years longer the doors that were closing around my father’s life.

Donna must have wished to spend that time with her own family instead of surrounded by three extra children who bossed her young brood mercilessly. She must have wanted an evening alone with her husband, an event that wasn’t going to happen with her nieces and nephew hanging upon the man they hero-worshiped. I never heard such a sentiment pass her lips.

Our last adventure together occurred in the mid-seventies. My sister had married and she and her husband had moved north of Grand Rapids, Minnesota, where they were managing Camp Layal, a Baptist church camp. If we could make the six-hour trip early in June before the camping season started, Jill told us, we could stay in the lodge, hike the woods, take evening rides on the pontoon boat, and canoe on the lake…all for free. It was an offer our penny-pinching gang could not pass up.

The blue station wagon was but a memory by this Time. Uncle Jim now sported a pickup truck with a topper. A mattress lined the floor of the truck, the end closest to the cab propped up with luggage and pillows. Into that makeshift bed we hoisted Dad, now much too weak to make a six hour trip sitting upright in a car. Three people sat in the cab, and we all took shifts sitting with Dad in the back of the truck. The balance of the gang followed the Hoey vehicle in the Stratton car. Our traveling methods had changed somewhat. Bathroom breaks weren’t as frequent or as urgent as during our younger traveling days. The 1974 oil embargo ushered in the age of self-serve gas, so filling station attendants were spared the vision of Dad’s prone body in the pickup. The one thing that hadn’t changed was the cooler full of cheap food. We devoured the sandwiches, fruit, and cookies at a roadside park along the way.

After a six-hour trip, we arrived at my sister and her husband’s trailer without incident. Mom and Dad stayed with them, but the rest of us slept in the camp lodge, invading the little trailer only at meal time. We had a wonderful time and so did the mosquitoes who feasted on a fresh infusion of sweet Iowa blood. Most of us, who had traveled before as children, were adults now or well into adolescence. Dan, the youngest among us, was about five, and having the time of his life running through the woods and paddling the canoes.

We were eating our meal together with the older generation seated around the table in the tiny kitchen, the rest of us spilling into the living room. Suddenly, from the kitchen, we heard Mom say, “Harlan, are you all right? Harlan, what is it?”

We all stood up and watched over the counter that separated the kitchen from the living room.

“Harlan, are you choking?” Mom asked.

Face red, nose running, he nodded. Mom and Jim pounded on his back to no avail. He began to turn blue. Jill tried to position herself behind the wheelchair to do the Heimlich maneuver, but the chair handles were in the way.

“Let’s get him out of the chair and on the floor,” Jim ordered. Mom and Jim reached around Dad and eased him to the floor, laying him on his side. Jill lay down behind him, her stomach to Dad’s back. Mom and Jim lifted Dad’s torso, and Jill slipped an arm beneath him.

The rest of us were frozen there, watching the scene on the floor. We were weak in our fear, praying that Jill could open the door closing on Dad’s life. Wrapping him in a bear hug, Jill squeezed Dad’s abdomen once, then twice, again and again, again, again, again. Jim and Mom held up the dead weight of his torso between them, allowing Jill room to maneuver.

Finally, we heard Dad begin to cough, and he sucked in a great wheezy lungful of air.Jill and Mom sat limply on the linoleum. The rest of us began breathing again, so mesmerized by the scene before us, we didn’t notice Dan’s big eyes taking in the frightening scene.

“You okay now, Harlan?” Jim asked in a hearty voice.

Dad nodded.

“You just rest on the floor a minute. Then we’ll put you in your chair.”

Dad nodded again.

Jim noticed Dan’s white face and went to him. “Uncle Harlan’s gonna be okay. That was kinda scary, wuddin’ it? Why doncha’ come over here and sit with me for awhile?” Dan and his dad went to rest with Harlan on the floor.

That day my Uncle Jim helped save my father’s life. To this day, long after my father’s death, the Stratton/Hoey gang crams into one house for a yearly weekend of good, cheap fun. I love to see my cousins and their children pull up and spill out of their cars, but I can hardly wait until Jim and Donna arrive. Donna wraps me in a big hug and kisses me on the cheek. Uncle Jim nods and in his Kansas twang says, “How are you, Jo?”

I go to him and let his arms hold me up as they once held my father.

by jphilo | Jun 27, 2014 | Reflections on the Past

Once again, a packed June schedule means there’s been no time to prepare a post for today. So once again, I dug into old writing files and pulled out a chapter from Lessons from My Father. That’s the book about growing up with my dad who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis when he was 29 and wheelchair bound shortly thereafter. It’s also the book that landed an agent, but has yet to be published.

Today’s story comes from early in the book and in Dad’s illness. It takes place in a short span of time when Dad’s father lived with our family and then entered a nursing home. This story caught my eye because of the reference to the Little Store. At our high school class reunion, we reminisced about that same establishment, which was a neighborhood grocery store that operated in a converted garage.

But the story is about much more than sweet memories of the Little Store. It is about one of the many losses my parents experienced in the late 1950s and early 1960s. As a child, I didn’t understand how their dreams were snatched away, one after another. Now, as an adult, I marvel at their ability to keep going during those sad years.

Grandpa Stanton

Grandchildren are the crown of old men,

And the glory of sons is their fathers.

Proverbs 17: 6

“I’m goin’ to the Little Store. I’m goin’ to the Little Store.” A surge of satisfaction welled up from deep within me as I sang to myself. My small hand fitted perfectly into Grandpa’s big one, and I reined in my high spirits. I attempted to glide beside him in a dignified, graceful manner worthy of his presence, and at the same time I quivered with anticipation of the delight that awaited only one short block away.

“What are you going to buy with your nickel, Jolene?” Grandpa looked down from his great height with a smile.

I looked up at him, comforted rather than intimidated by his stature. I liked looking up to him, an act not necessary when I walked beside my father’s rolling chair. I pondered my answer while avoiding the cracks in the sidewalk. Notoriously clumsy, I didn’t want to trip and fall, ruining this delicious outing. “Whaddya think I should get, Grandpa?”

He always gave me, one of his only three grandchildren, thoughtful advice which my other grandpa with three times as many descendants to his credit never had the time to offer. “Do you like gum? You could buy a pack and share it with your family. Five sticks. You’d have just enough.”

Mentally, I flushed that idea. Grandpa had given me a whole nickel to spend on myself. No way was I going to share. “Nope, I don’t like gum.”

“Do you like candy bars?” he probed. I liked this about my grandpa. Mom didn’t have time to find out what I liked, and Dad didn’t always have the staying power. Neither of them had nickels to squander on candy from the Little Store, but Grandpa Stanton did, at least during this most fulfilling interlude, a short April to November, when he lived with us. He lavished upon his grandchildren the time, attention, and nickels they loved.

“Chocolate, lots,” I confessed.

“Do you like nuts?” He knew just the right questions, always.

“Uh-uh.” That I knew with certainty.

“Then I,” Grandpa counseled with great solemnity, “recommend a Milky Way.”

We walked into the Little Store, and I looked at the candy rack. Grandpa was right. A Milky Way was just what I wanted. I placed the candy bar and my nickel on the counter.

“This somebody special, Jolene?” Mrs. Manning asked as she rang up the sale. She recognized all the kids in the neighborhood. Most of them purchased candy and pop from the tiny shelves that lined the garage she had outfitted as a neighborhood grocery store. The Stanton kids only came for a loaf of Wonderbread or a half-gallon of milk when those staples ran out mid-week. She correctly deduced that this candy purchase was a noteworthy event. I, however, was surprised by her question and gaped at her, speechless and flustered.

“I’m her grandpa, Cyril Stanton.” Grandpa reached across the counter, shook her hand, and then gave me my candy bar.

“He lives at our house now. He gave me a nickel.” Grandpa’s rescue primed my pump, and I added the important details to Grandpa’s rather sparse introduction.

“Pleased to meet you, Mr. Stanton. I’m sure Harlan enjoys having you there.”

I clutched my candy bar in one hand and slipped the other back into Grandpa’s, pulling him out the door. I didn’t like sharing my time alone with Grandpa. I hung from his arm for our entire two block walk, waiting to open and eat the candy bar, an act that required two hands on my part, until I got home.

“Thanks, Grandpa.”

“You’re welcome, Jolene.” I smiled up at him, and his eyes smiled down at me beneath the black, bristly eyebrow so thick there was just one that went all the way across his face. I walked as slowly as possible, determined to eek as much pleasure as possible out of the short trip. I was convinced that heaven, at least the one described by my Sunday school teacher, couldn’t be much better than this.

Having Grandpa live with us seemed a heaven-sent solution when he first arrived. His diabetes had become more troublesome since Grandma Stanton died, but for years Grandpa continued to live and work alone in Nevada, Iowa, visiting our family often. When he went into insulin shock while driving one day, his car stalled on the railroad tracks. A swift rescue by the local police saved his life, but not his liberty or happiness. His driver’s license was revoked, and he was stranded. Living with us gave him places to go and people to see, and a way to get to both. For awhile the arrangement seemed like it would work. At age six, I thought life couldn’t get any better, but there was lots about adult life that I didn’t know.

I didn’t know that my grandpa who looked so young, with a full head of black hair barely flecked with grey, was going into diabetic shock often. My mother had to get up each night to check on him and correct the imbalance with an orange juice and sugar midnight cocktail. Even my sister knew the signs and gave him orange juice as needed during the day. I didn’t know that when school started in the fall, Mom was so tired from interrupted sleep that she could hardly drag herself to work. I didn’t know that my grandpa, who always acted so calm and caring and looked so dashing in the short sleeved sports shirts he wore unbuttoned at the neck, was losing his sense of judgement. I didn’t know that my grandpa, who gave us handpicked gifts like carved wooden wishing well banks from Canada and red felt cowboy hats with white trim as well as savings bonds for college, had kicked my misbehaving little brother one day. I didn’t know for many years that those were the reasons for my mother’s announcement one night.

“Grandpa Stanton isn’t going to live with us anymore,” Mom explained as we finished supper. “He’s going to live at an old folks’ home in Cedar Falls where there are nurses to take care of him and lots of people to talk to.” She tried to give it a good spin. “Grandpa even knows the director. He was the minister in Nevada when Grandma Stanton was still alive.”

I didn’t know that our minister had been so concerned about Grandpa’s situation that he had come to school, taken Mom out of class, and asked what he could do to assist her. I didn’t know that he had called the director of the Evangelical United Brethren (EUB) Home and made all the arrangements. All I knew was that I didn’t want this grandpa to leave, and I couldn’t imagine that my dad could want his dad to go.

We drove Grandpa to the home the day after Thanksgiving. Earlier in the week our minister had contacted the director of the home, effectively conveying the urgency of the situation.

“We have an opening right now, and we’ll hold it for Cyril,” the director and old friend agreed.

“The only thing is, he has to be able to walk in on his own.”

Mom knew Grandpa was failing fast, so as soon as the turkey leftovers were tucked in the refrigerator, she helped him pack, and the next morning we scrambled into the car. We were a pretty somber crew on the way over, but once we got there, from my vantage point, the old folks’ home was a great place to visit. Of course, I didn’t have to live there. A big statue of a lion stood outside the imposing front door of the many storied brick building that I was sure covered at least three city blocks. As honored grandchildren, we were allowed to climb on the lion and “ride” it. I took the honor very seriously and religiously performed my duty each time we went to see Grandpa.

Once we entered the building, scores of ancient eyes fixed upon us, wrinkled lips croaked greetings. “Look, Mabel,” I heard one starved voice marvel, “children.” Fluttery, shaking hands, moths to a flame, reached out to touch me as I walked by, and I shrank away, moving close to my father’s wheelchair. Sour smells, like the inside of my dad’s urinal, swirled around me, making my nose squinch shut and my mouth wrinkle.

“Jolene, get rid of that face. You’ll hurt their feelings,” Mom whispered.

I tried to smile, but every pungent, sharp breath twisted my face into a lemon. Our shoes clicked on the shiny floors of endless tomblike hallways until we stopped at the doorway of a small room. Grandpa put his luggage on the bed and unpacked. Once he was settled in, we stayed for dinner and visited awhile, gaining fortitude for our return trip which was over three hours tacked on to the three hours plus we’d spent getting here.

Our presence in the dining room presented a political problem. “Why,” one white-haired matron asked a dining room staff person, “do all three of those perfectly darling children get to sit at the same table? It is not fair.”

I searched the dining room, which I estimated was as big as a high school gymnasium, for the three “perfectly darling children”, but couldn’t find them.

“Jolene,” Mom asked, “would you be willing to go sit at the table with that lady?” She pointed to the outspoken matron. “She doesn’t get to eat with children very often. Try and get rid of that sour face and smile,” she advised. “John, you could go sit at that table with those nice men, and Jill, you can stay right there by Grandpa.”

Us? We were the “three perfectly darling children”? I was dumbstruck but willingly trotted over to the white-haired matron who was pulling an empty chair up close beside hers, motioning me over. “Well,” I wondered, “how’m I gonna act ‘perfectly darling’?” By the end of the meal, I was still clueless, but none of my tablemates seemed to mind. They just kept patting my head, offering to cut my meat, asking me questions, treating me as if I was “perfectly darling.” I was basking in the limelight, filled to the brim with the extra desserts they had passed on to me. “Whadda place to live,” I thought. “Grandpa’s got it made.”

Grandpa didn’t have it made. He was lonely, and we visited as often as we could, but the trip took a whole day, and even though we were “perfectly darling children” the moment we stepped into the old folks’ home, we were not always so on the trip there and back. Our first few visits chased away Grandpa’s loneliness, and our entrance into the dining room delighted him to no end.

“Look, Cyril’s darling grandchildren are here again” the cry would go up, and he chuckled as he watched the diners fight over us, the victors carrying us off as spoils to their table-length fiefdoms.

When we went outside for a walk with Grandpa, he handed us dimes. Yes, dimes. “Do you hear that bell?” He and Dad grinned. Mom steered Dad’s chair toward a bench where she and Grandpa sat down.

A magical tinkle of chimes drifted towards me. “What’s that?”

“The Good Humor Man,” Grandpa explained.

I looked blank. My dad was right beside me. Who else could be the “Good Humor Man?”

“The ice cream truck,” Dad translated.

“Oh.”

“Go on,” Grandpa coached. “Wave to the man and buy a treat.”

I obeyed and ran after my sister and brother to the truck. All the way home I tasted the ice cream bar Grandpa’s dime had bought.

I anticipated similar delights as we drove in the parking lot for our next visit, but they weren’t forthcoming. When we got to Grandpa’s room, I noticed his hair was still black, but he looked lots older. When we walked in to greet him, he didn’t look at any of us, just cocked his ear in the direction of the sound. His eyes were vacant, blinded by diabetes, and he couldn’t see how perfectly darling we looked that day. During the following visit we stood beside the bed where he lay unaware of our presence. By Thanksgiving, barely a year after he went into the home, he was dead.

I was too young to grieve, more than superficially, and so was my brother. Grandpa’s loss to me was a loss of creature comforts: unexpected dimes and nickels, a lap to sit upon, a smile that made me feel very loved, a hand to hold, a friend to talk to.

For my father and mother and sister, the grief was much deeper and wrenching. They had lost the one person who had time to give them the wholehearted emotional support they needed. My father and mother lost the last person who had shared their original vision of a hopeful future. My father, without brothers or sisters to comfort him, lost the most enduring link to his childhood.

While I had lost a bearer of sweet gifts, my father had lost his bearings.

by jphilo | Jun 13, 2014 | Reflections on the Past

The first Sweet Vidalia onions of the season appeared in our grocery store this week. Their presence brought to mind a chapter of the first book I wrote…the one about my father that led to an agent but not to a contract. Not for this book, at least. So today, in honor of Father’s Day and Sweet Vidalias, enjoy this chapter from the unpublished manuscript. It’s much longer than my usual posts, but the timing is perfect. This story takes place right after Mom, my sister, brother, and I meet with the undertaker and decided to purchase plaid boxers for Dad to wear at his funeral…under his suit, of course.

Courtin’ Onions

So then, you shall know them by their fruits.

Matthew 7: 20

The underwear dilemma successfully resolved, a multitude of decisions rushed in to fill the vacuum created in its wake. What kind of casket? The farm scene one, of course. How sturdy a vault? “The cheapest one,” we chorused, all remembering Dad’s comment at the same funeral home when selecting his father’s final resting place over thirty years before. “Why buy the most expensive vault, guaranteed to last who knows how many years? They’re just gonna’ bury the thing, for Pete’s sake,” Dad declared, leaving little doubt where he sat on the issue.

We honored his wishes and soothed our own frugal souls, sticking to the bargain basement model. We chose the bulletin with the windmill and the Scriptures about endurance and rising up to walk. Some controversy arose concerning the music for the service. We kids wanted The Old Gray Mare, I’ve Been Workin’ on the Railroad, and Sioux City Sioux, but Mom held out for more traditional fare, allowing Dad’s Passenger Seat Top Forty a brief airing during the luncheon after the service and internment.

Great-uncle Burnell, a former plumber and pipe layer whose memory contained a map of the entire underground terrain of Nevada, Iowa, where Dad was to be buried, was on the phone. He assured us that he was consulting with the cemetery crew concerning the exact location of Dad’s future digs.

“Say,” he hollered over the phone, after describing in detail the precise drainage characteristics and soil qualities of the earth Dad would displace. His raspy voice grated across the wires like gravel, “Anybody told Willie ‘bout Harlan bein’ dead? Want me ta go over and do it?”

Mom held her hand over the mouthpiece and whispered, “Burnell wants to know if he should go tell Willie. What do you think?” She hesitated. Burnell had a heart of pure gold, but when in the presence of strong emotion he lacked skill in the tact department, and his best intentions were sometimes misinterpreted.

“Tell him that you and I are going to see Willie,” John advised Mom. “Tell him you want to visit Willie yourself.”

Willie New was a shadowy figure from our parents’ past, one of the people they often spoke of but rarely saw. Once Dad and Mom left Nevada, the small central Iowa town where they lived for the first three years of their marriage, Willie hovered around the edges of their lives, seldom making an actual appearance. Willie and Dad met when both were young men farming near Nevada. They shared a love for cattle that bonded their friendship. Each was his parents’ only child, so each filled for the other the empty space in their lives. Willie filled that space amply, for he was a big guy. Standing beside Dad, grinning proudly from his place of honor as best man, Willie is the only person in my parents’ wedding party whose cubic footage topped the groom’s. Holding the ring and passing it on was as close as Willie ever came to a wedding band, and his bachelor life suited him just fine.

On trips to Nevada, Dad and Willie occasionally visited, though Willie didn’t like crowds too much. Mostly Willie kept in touch through the sending of an annual Christmas card, but we learned more about him via the grapevine gossip Dad’s two elderly aunts passed along from time to time.

“Tell Harlan,” Aunt Ginnie’s voice gained volume when talking long distance in an effort to push the words along the miles of wire. “Tell Harlan Willie’s building himself a little house in town. He don’t think it’s safe for him to live on the home place alone, now that his parents is gone.”

“Harlan,” Aunt Gladys wrote in Dad’s birthday card, “Willie New, your old friend, he just found out he’s got the diabetes, just like you. Hit him awful bad, he’s not doing a bit good, and he just don’t get out much anymore. He’s still livin’ in that new house he built, and someone comes in to check on him. I heard it at church circle and thought I’d better tell you. Sorry the news isn’t any better from down here, but we’re all getting old, you know.”

Mom and John headed to Nevada, to that new house of Willie’s, to tell an old man that the friend of his youth was dead. They were somber as they left on the errand, unsure of how Willie, in his own fragile state of health, would handle the news. When they returned from the mission, the smiles on their faces told me a story was in the works.

“How’d Willie take the news?” Jill and I waited impatiently as they entered the kitchen and sat down before answering.

Mom was chuckling as she began to talk. “Well, we told Willie, and he was quiet for awhile as you’d expect. Then he said, ‘Dorothy, I don’t think I’ll come to the funeral. I don’t get around real good, and I don’t like crowds much. Maybe Dick Suttle, he helps me with my shoppin’, ya know, can bring me to the funeral home. I’d like to see Harlan one more time.’ I told him that was a good plan, and I understood that he couldn’t come to the funeral. Then we talked for a bit, and you’ll never guess what Willie said.”

John sat on a tall stool at the kitchen island, the grin on his face assuring us that the best was yet to come. “Willie’s quite a talker, you know, very smooth…” he began.

Mom interrupted, not willing to let John steal her thunder. “Willie said, ‘Dorothy, you took care of Harlan all those years. He couldn’t have asked for a better wife. You got nothing to be ashamed of, ya know that?’ I told him I knew that, and then he said…I just can’t believe he said this…”

“He made her quite an offer. You want me to tell ‘em what it was?” John nudged the story along.

“Alright, John, let me finish,” Mom snapped. “Willie said, ‘Dorothy,’ in that high nasal voice of his, ‘Dorothy, you get lonely, you can come live with me. I got a whole apartment in the basement. You could live down there and come up here and take care of me. You could even drive that Cadillac I got sittin’ in the garage out there.’”

Jill and I looked at one another, and I wondered if she was having as hard a time as I was imagining our frugal mother steering a blatantly extravagant Cadillac around Nevada, Iowa. Jill burst out, “I certainly hope you told him no.” Apparently the horror of Mom jumping out of the frying pan of Dad’s convalescence into the fire of Willie’s failing health took precedence over the Cadillac vision for her.

“Told you it was quite an offer,” John teased.

“Of course I told him no, but I had to do it nicely. ‘Willie,’ I said, ‘I’ve spent most of my life raising kids and caring for a sick husband. I believe I need a break. I’ve had enough sickness, don’t you think?’”

“Let him down real easy, didn’t she?” John baited her. “He was a little disappointed, but I think he’ll recover.”

“John, let me finish this story. Willie said, ‘Dorothy, you’re right. You don’t need no more sickness. I understand.’ I told him I would visit him now and then. I think that helped.”

“Don’t you ever, ever say yes to an offer like that,” Jill lectured Mom. “You deserve your own life now.”

“Don’t worry, Jill, I have no intention of tying myself down. I made myself perfectly clear.”

Willie, however, was not so easily discouraged. He made it to the funeral home for visitation, shuffling along behind his walker, across the long room to where Dad lay in the casket with the farm scene decorating the shiny satin underside of the lid. Willie looked at the carved wooden cow held in lifeless hands and bowed his head for a long time. “Dorothy,” he shook himself out of the past he had shared with his friend and spoke as she came up beside him, “ya done good. He woulda liked that.”

“Thanks for coming, Willie. It means a lot.” Mom shook his hand and hovered over him as he shuffled out of the room and down the stairs outside.

“Mom,” we teased her when she returned, “quit leading the poor man on.”

“Would you three just stop for once,” she retorted and huffed off to talk to Uncle Burnell and Aunt Ginnie.

A month or two later, Mom called and said, “You’ll never guess who stopped by.” I didn’t even try. “Willie New!”

“How in the world did Willie get to Boone? He can’t drive can he?”

“No, Dick Suttle brought him over.”

“What for?” I was getting curious.

“He likes to shop at Peoples’ Clothing downtown. They carry work clothes in big and tall sizes. Willie said he gets most of his clothes there.”

“So he stopped in to say hi when they were done. That’s nice.” The visit was starting to make a little more sense. “Did he and Dick stay long?”

“That’s the funny part, Jolene. Willie didn’t even come in. The doorbell rang and I opened the door, and there he was, holding an onion in his hand.”

“Did you say ‘an onion’?”

“Yes,” Mom laughed. “He stood there holding the onion. ‘Sweet Vidalia,’ Willie explained. ‘I buy ‘em in ten pound bags every spring and take them ‘round to all my friends. They’re a real sweet onion. This’uns for you, Dorothy.’ I really didn’t know what to say,” Mom went on.

“Sounds like he was making a move, Mom,” I couldn’t resist. “Did you invite him in?”

“Good grief, Jolene. He said he couldn’t stay, he just wanted to give me the onion.”

“You know what that sounds like to me?” I asked.

“What?”

“I think that was a courtin’ onion…”

“Jolene!”

“Well, Mom, some men give flowers, some give candy, but Willie has it all over them. He brought you an onion. You better be careful or someday he might bring you the whole ten pound bag.”

“Would you please stop?”

I couldn’t wait to share the story with Hiram and the kids when I got off the phone. Then, I called my brother and my sister.

“Smooth, that man is smooth,” John boomed over the line.

“An onion? An actual onion?” Jill double checked the facts.

“Not just any onion,” I corrected. “A Sweet Vidalia.” We laughed until we cried imagining Willie at the door, paying homage to my mother, recognizing and honoring her faithfulness with the humblest of gifts. A rose by any other name could never have smelled as sweet.

When sweet onions are in season, I only buy the Sweet Vidalias. I pass up the red onions, the Walla Walla Sweets, and the Colorado Sweets, and head straight for the courtin’ onions.

“Courtin’ onions are in,” I call and tell my mother when I first see them in the store.

“Jolene.” The one word is tinged with impatience as I exasperate her again.

I can’t find words to tell her what those onions and Willie’s offering of them means to me. “We are known by our fruits,” Jesus said, and as I look at my mother’s life, I know that is true. She finished school, raised three kids, taught for thirty-eight years, and through it all cared for her husband, never thinking of walking away. The strain of it nearly broke her a few times, and she was too stubborn to seek or to accept help, too proud to admit weakness, too determined to do it all alone. But, the mistakes she made were covered by her devotion to a righteous cause and her absolute commitment to the promises she made in her wedding vows. God knew her heart and, when her duties were done, honored her with a fruit that matched her character, delivered by a messenger who knew her worth.

The fruits of the spirit are love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control; but if possible, I would like to enter into that exalted list one more: a Sweet Vidalia onion, hearty and healthful, its zippy bite tempered by sweetness, its flavor permeating whatever dish it graces. Its presence there stands, at least for me, as a perfect reminder of my mother’s extraordinary and fruitful life.

Photo Source

by jphilo | Apr 18, 2014 | Reflections on the Past

Comfortable and casual as our lives are now,

When Easter rolls around,

With barely a nod to Palm Sunday,

Maundy Thursday,

and Good Friday,

I wish for more.

I wish for fish on the school lunch menu every Friday during Lent,

For a Holy Week marked by children waving palm fronds on Sunday,

For hushed and humble communion on Maundy Thursday evening,

For no school on Good Friday,

For Saturday evening watching Lawrence Welk while Mom puts curlers in my hair,

For fitful sleep in my beauty crown of thorns,

For hunting eggs on Sunday morning.

I wish for the struggle of pulling on tights and a itchy petticoat,

For anklets and Mary Janes on my feet,

For getting tangled in a new dress,

For Mom combing my feeble curls,

For the glory of an Easter hat and gloves,

For a dime tied in a hankie and tucked in my purse,

Ready for the offering plate.

I wish I could go to church with my family,

Scratch where the petticoat tickles my waist,

Gaze at the stained glass windows and

Wonder if Jesus’ brilliant white robes were itchy, too,

Stand when the organ music swells us to our feet,

And with a child’s untested perfect faith sing,

Christ the Lord Is risen today,

Alleluia!

Those Easter bonnet days are fifty years gone,

But the child within me still lives,

And my faith,

Now tested and imperfect,

Now internal and personal,

Rather than external and tradition,

Lives as well.

Clothed in Christ,

I stand and sing

To the timeless God who wore a crown of thorns,

Who bore my sins on the cross,

Who died so I might live,

Jesus, the Son of God, is risen

Today,

Yesterday,

Fifty years ago,

And forever.

Alleluia!

by jphilo | Jan 27, 2014 | Reflections on the Past

Thanks to the cold, snowy weather this month, residents of the northern two thirds of the US are fighting the winter blues. From the sounds of things, the light at the end of the winter blues tunnel won’t be shining any too soon. So on to Plan B, which is a couple stories from the Harding County History Book erased my winter blues and inscribed a couple mental notes upon my brain for easy access when that blue feeling creeps up again.

Here’s an excerpt about the winter of 1897, the first year the Finnish immigrants Andrew and Alina Peterson lived in northwest Harding County.

Andrew dug into the hillside and made a one-room accommodation for Alina and the two small children, Blanche and Sulo. The first winter Alina lived there without Andrew as he went back to the Lead gold mine to work. Alina baked bread and traded it for meat with the passing cowboys who had a camp three or four miles away. One remembered story told of a time when a cow wandered away from the herd and suddenily fell through the sod roof and into the middle of the one room home. No one was hurt, though there was quite a mess to clean up as well as roof repairs.*

The second excerpt comes from the Elliot family, about a March snowstorm. The exact year isn’t given, but must have been before 1910 based on other dates mentioned elsewhere in the account.

The snow drifted clear over the door that night. Dad had to dig his way out with the coal shovel to get to the pump. The storm lasted three days and then a thaw came. The creeks were full of slush and another blizzard came, which lasted three more days. We ran out of coal, all but the slack (the tiny particles and dust left after the larger pieces are gone). Dad went to the shed and found some old beef bones, he put them in the big heating stove on top of the slack while it was burning. It didn’t smell too good, but kept us warm. He finally pulled a bobsled into the big kitchen and sawed it up for kindling.**

*Note to self: Stop feeling blue about how the lack of a mud room entrance in our NINE room house (not counting the basement) means mopping the tracked in melted snow and gravel off the kitchen floor. Store the complaining in a safe place and let it rip when a cow falls through the roof.

**Note to self: Instead of feeling blue about how high your heating bill is this winter, inhale deeply and enjoy the lack of burning bone odor in your house. Stand in the kitchen and enjoy the quiet created by the lack of a bobsled being chopped into kindling.

What helps you beat the winter blues? Leave a comment!

by jphilo | Jan 20, 2014 | Reflections on the Past

The Great Purgeal Vortex of 2014 continues unabated at our house. This weekend it unleashed its fury upon our unsuspecting and completely innocent kitchen. The that raged inside our kitchen cupboards and drawers revealed some unexpected treasures, mostly in the form of old cookbooks and recipe files inherited from my mother-in-law.

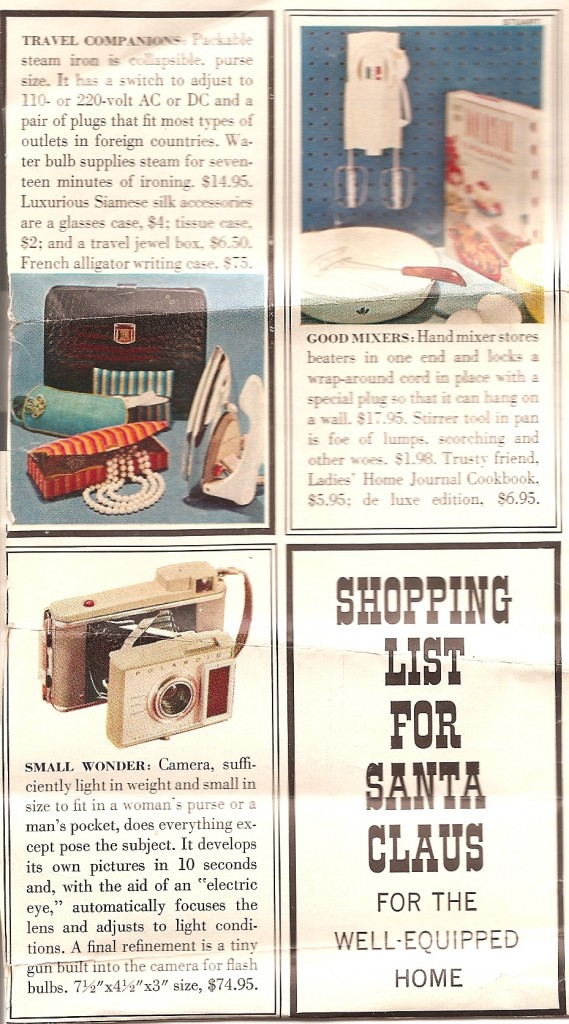

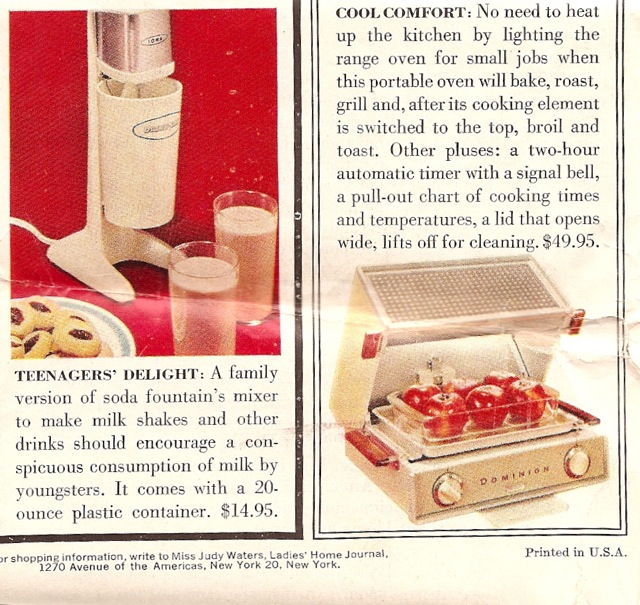

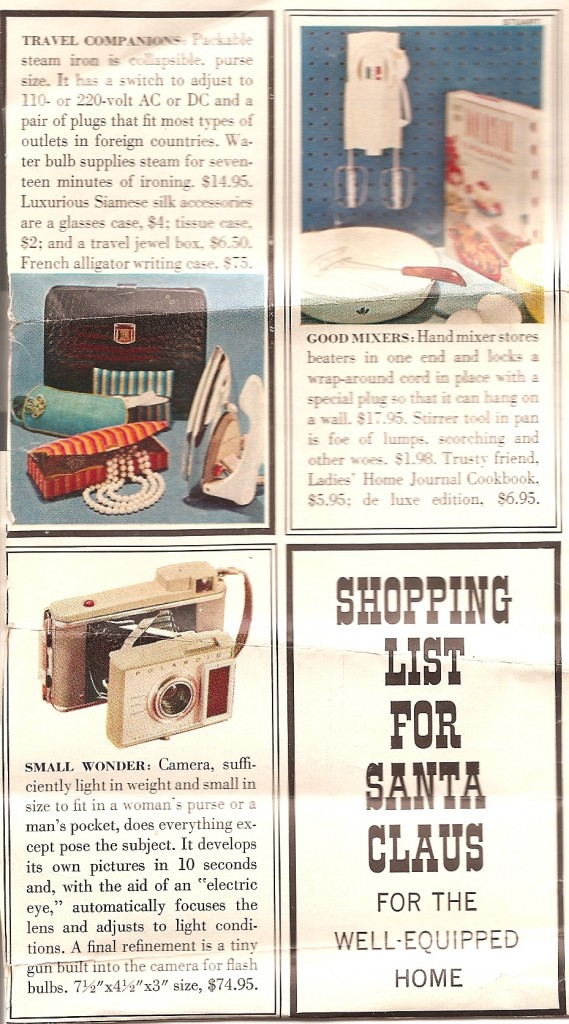

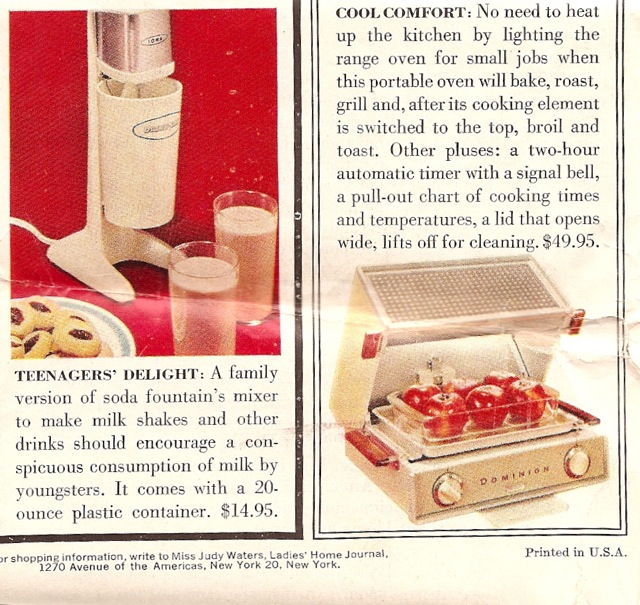

One file was filled with recipes found in booklets slipped inside baking products, ripped from magazines, and clipped out of cereal boxes. But the backside of a page of Christmas recipes torn from the December 1961 issue of the Ladies Home Journal contained a shopping list for Santa Clause for the Well-Equipped Home. For those of you planning a retro-themed Christmas for next December, the first half of your list is located at the top of this post. The second half is directly below.

Just so you know, my siblings and I did not grow up in a well-equipped home. At least not according to Ladies Home Journal standards. In the interest of full disclosure, I must admit that Mom did have an electric hand mixer, but not one that hung on the wall. She also had cookbooks. But they were published by Betty Crocker, not Ladies Home Journal.

However, as a kindergartener in 1961, I coveted, coveted, coveted the milk shake mixer. But at $14.95 it wasn’t coming to our house. Neither were the travel items, as we didn’t travel much. And the portable oven and the camera “sufficiently light in weight and small in size to fit into a woman’s purse or a man’s pocket” were way, way out of reach for a school teacher’s salary.

The ad begs a couple questions, which you can respond to in the comment box:

- Which of these items made your home well-equipped in 1961?

- Do you think Don Draper or Peggy Olson from Mad Men came up with the idea for this ad?